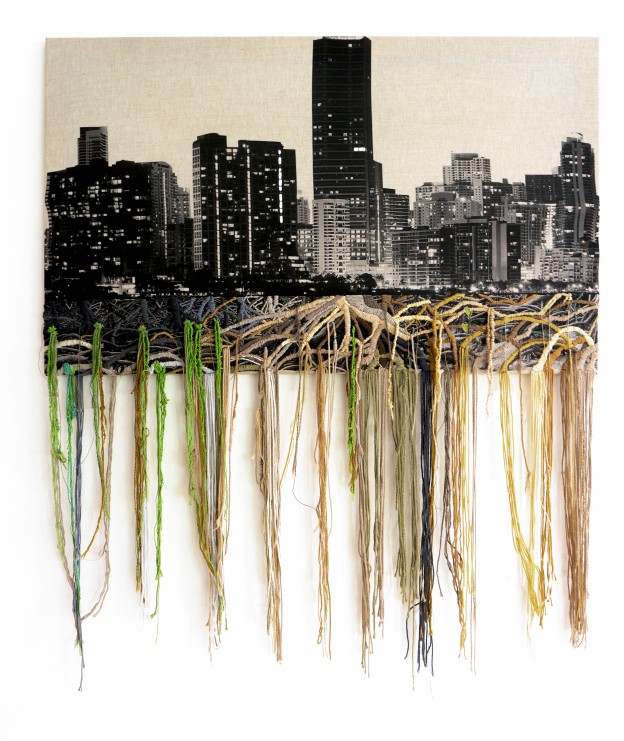

Past Exhibition

UJAMAA: Inertia of the Vine

Works by Ernesto Oroza

From December 5th to January 15th/2013 at Aluna Art Foundation | Focus Locus

An installation that derives its name from a political group which sought in Africa the utopia of collectivism accounting for traces of anonymous and collective forms of creation, in which the fatality of nature and culture constitutes not only a symbiosis but a cycle of endless return.

Aluna Curatorial Collective

Ujamaa (The Bejuco’s Inertia)

By Ernesto Oroza

The Bejuco (climbing woody vine of the tropics) is the son of Dadá. The Bejuco, which has the same autistic inertia as Kurt Schwitter’s (1) “Merzbau”, is the son of Dada Baldoné, the Yoruba goddess of vegetables.

A rural ─and strangely universal─ myth asserts that all the bejucos are only one –an interminable one. It is even said that there is a great circle. Others speak of many “bejucos” forming closed loops, huge plant rings where the logic of the infinite is multiplied. In any case, if you find an end, it means that a circle has been broken.

The persistent and whimsical strength that inhabits the bejuco lies hidden in the city. It animates some bodies, collapses others; it nourishes unexpected flows. The accumulations of wood around some trees in the city come to my mind. The wooden trunk, processed and “shrunken”, returns to its origin. Baldoné, who is bejuco sap and guizazo seeds, shakes the vegetable kingdom, rejects the carpenter’s epiphany: the technological grain and edge. Wood is wood. The movement of the stick in the city makes a loop.

From tree to tree, it closes a circle. In the meantime, because that is what Dadá permits, the trunk is subject of labor, time unit, exchange value, subject to rule. Or at least it is ideally that. There were things cannot be named as Home Legend Honey, Marazzi Imperial Slate, Three Rivers Gold Slate – where Home Depot has not yet arrived – materials are subjugated by the force of need, that latency as powerful as the bejuco, which can contain a coffee field or drown a river.

* (1) This name designates the ongoing transformation process of the artist’s family house in Hannover, one of the greatest artworks of the 20th century given its imbrications of the multiple dimensions of the relationship between art and life, even though it was destroyed during an air raid in 1943*

Objects of necessity

By Ernesto Oroza

In certain contemporary urban areas the necessity generates objects that look more the result of an unavoidable sedimentation of materials cornered by the wind into the shapes of the city than the result of a productive activity.

Broken metal chairs loosen from a school and plastic chairs, also broken, expelled from a cafeteria, nearly one piece each month, they ramble around the neighborhood until they get tangentially trapped inside a human activity: a security guard, a street vendor, a ruined bus stop, a mechanic having his business on the sidewalk. It happens everywhere at the same time, as if a hypothetical grid formed by all the broken plastic seats in the city fit by gravity with the gridded field of metal broken chairs spread years ago around Havana. The necessity generates a fatal equation that, under similar circumstances, produces the same results. The individual in need will focus exclusively the repertoire of the usefulness, propitiating a conjunction, a harvest time.