PAST EXHIBITION

The Global South: Visions and Revisions from The Brillembourg Capriles Collection

Curated by Adriana Herrera and Adolfo Wilson

A “SaludArte” project by invitation of Mana Common, parallel to Pinta Art Fair, Miami 2016

Tanya Capriles Brillembourg | Founder & President, SaludArte Foundation

To travel the broad artistic journey of our continent requires an ambitious and uncertain endeavor. The Global South, Visions and Revisions of the Brillembourg Capriles Collection, leads us through a retrospective exercise of a past which defines our present, thus opening up a path which others have traveled: so as to find out why history has been told with such gaps which distort the essence of Latin American art. The exhibition aims to help in this search, to dissipate such lapses which have brought us to forget, omit, silence and do away with a more inclusive realization of our continent’s art, bringing us closer to its historical reality, in open contrast with the purported version told from the perspective of the epicenters from the Global North.

This is a responsibility I have undertaken since I started the SaludaArte Foundation in 2003 in Miami. In which cultivating the arts joins the quest of transforming people, by promoting the necessary social changes to insure they have a more promising and dignified future. A good example of this endeavor is the “Viola Meets Mozart” performance, which we are co-producing with Mana Common in their Wynwood location and will be staged on November 29. In it music, dance, and video art fuse into a single surging emotion, manifesting what art is all about.

THE GLOBAL SOUTH

By Adriana Herrera and Adolfo Wilson

Could a linear construction of history, and thus of the history of art, be sufficient in such a complex and contradictory geographic area as Latin America, where, as stated by Alejo Carpentier, the past and the present coexist? This question, posed from the Brillembourg Capriles Collection—mostly conformed by Latin American geometric abstraction and parallel explorations from Spain and Portugal in the 20th and 21st centuries, and even from South Africa, as part of the new global South—has led us to privilege a diachronic approach, with an open view of history in construction, full of intertwined temporalities.

Since we know that geopolitical representations affect artistic representations and their own visibility, we suggest seeing the South not just as a region, but as a perspective that seeks to expand on the idea of the América invertida (Inverted America) by Joaquín Torres-García. In this manner, this curatorship suggests an expanded map conformed by subject-territories, a dialogical learning of the revisions of art, and it recognizes the currency of and an acknowledgement of the validity in both hemispheres of the Manifiesto Antropológico (Anthropological Manifest) by Oswald de Andrade.

Great collections can play a key role in this effort to review the history of artistic movements, processes and practices in the entire world. The Brillembourg Capriles Collection includes a selection of Latin American masters as well as forgotten or not sufficiently recognized Hispano American pioneers. Though it encompasses works reflecting the dream of modernity, it also incorporates contemporary pieces that subvert it. This curatorship proposes a non-linear, non-hegemonic vision, in terms of chronology, of approaches between quite distant frontiers and movements, as well as a dialogue of masters and not-well-known pioneers, including those which defected the hard road of geometric abstraction.

The subtitle of the exhibition called El Sur global evokes the words with which Octavio Paz himself referred to El laberinto de la soledad, a crucial book that in 1950 was already addressing the issue of peripheric and marginal countries against dominant countries, of object-countries and subject-countries; a book he described in a postscript in 1970 as “a critical exercise of imagination: a vision and a revision.”

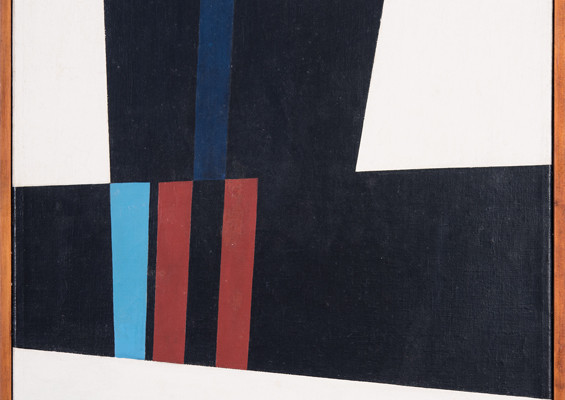

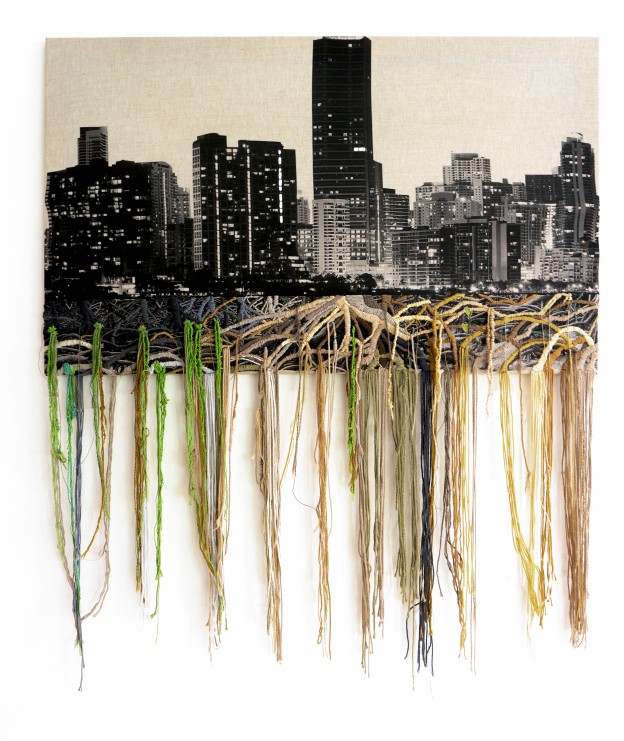

“SOUTH-VERSIONS” (SUBVERSIONS) OF THE GRID

If one sets out to talk about the grid, quoting Rosalind Krauss is inevitable. Her penetrating vision of the grid as the matrix of modernity exposed the latter’s spatiotemporal foci. The grid’s pure form radically transformed the relationship between form and content, neutralizing their opposition, and allowed artists to finally leave aside the notions of sequence and narrative, as well as the need to make reference to a setting. But beyond acquiring this profound insight, Krauss recognized in the grid the force that was driving the future, an atmosphere of aesthetic rebellion which a century later still generates works reflecting a self-contained universe: non-referential, a flat, geometrically ordered works. The grid and the lattice were the elements behind the entire production of geometric and meta-artistic art.

This section addresses on the one hand how that visual expression of modernity made its way to Iberoamerica, informing the artworks of many great masters of geometric abstraction in the Global South, characterized for a broad diversity associated to the very history of the continent. The Brillembourg Capriles Collection offers a revealing journey through the dynamics of construction and deconstruction of the grid, and shows not only the subversive attitudes against initial dictates of the European modernity, but also on behalf of the Latin American masters who during their own time had put in place their dissidences. This exploration includes the works of belatedly recognized or forgotten pioneers. Moreover, a key contribution of this Collection reveals the subversions of the grid having as its counterpart the utopia of architecture with its promise of modernity for all of Latin America. The lesson contained in the aftermath of the grid, subverted by varying perspectives of imagination, emerges as a response to the daily needs, emblazoning other strategies of artistic and social transformation.

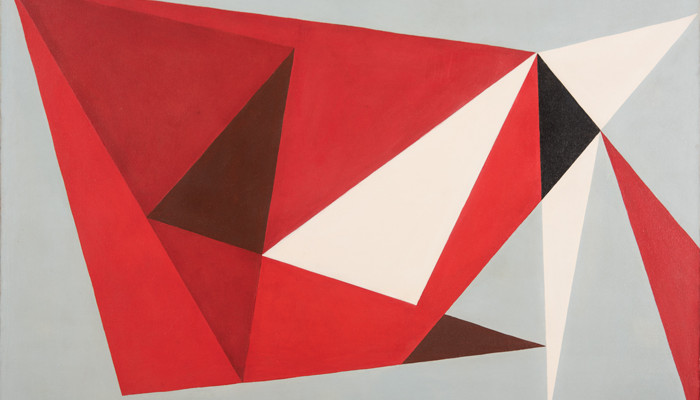

“UTOMETRIES”

“Utometry” is a neologism describing the close relationship between Geometry and Utopia both apparent in the aspirations of the constructivist vanguards much in the same manner as in subsequent pioneering movements in Latin America. The urge to transform the conception of art and the sensitive models of perception paralleled the need to change the vision and construction of reality. The invention of a different, possible world from the point of view of geometry was an aesthetic-political longing shared and thus expanding Thomas More’s isle of Utopia.

The Brillembourg Capriles Collection allows for a view to the different aesthetic insurrections advanced by major representatives of the Geometric Abstraction but also to works by newly-discovered artists, and to certain pieces which depict for instance how in Cuba the development of geometric abstraction was paradoxically hampered by the dictums of the new revolutionary epic. Finally, the Collection shows the contemporary re-appropriations of geometry and the displacements toward conceptualism in the Global South, opening a dialogue with parallel inquiries from other parts of the world. Some works reflect the budding relationship between geometric formats and different types of archives using textual sources or historical objects such as flags. This type or art supposes the appropriation and deconstruction of the idea of untainted geometry, and the game with geometric appearance to approach situations of political and social uncertainty. A key element is the verification of the fact that, unlike the “utometrists” of the earliest vanguards, 21st century artists neither sign manifestos nor create movements; but instead of pretending to be at the end of the history of art after the collapse of the great narratives (Arthur C. Danto, 1984, 1997), they play with the possibilities of imagination by a ludic approach of multiple utopic isles or banners. Only the modernist notion of a single path is abolished.

“COSMIC PLAYFULNESS”

In the quest for an identity of its own, often driven by the principle of otherness, Latin American art shows from its inception a sort of vocation for the ludic, and also a fascination with the cosmic. Frequently, both notions converge to be expressed in a simultaneous, interrelated way. In the first half of the 20th century, an important segment of our continent’s art gathers the cosmogonic inquiries of pre-Columbian cultures, aspiring to articulate an iconography and develop a collection of themes capable of giving a plastic shape to its own cultural identity, but in the context of an achievement of modernity.

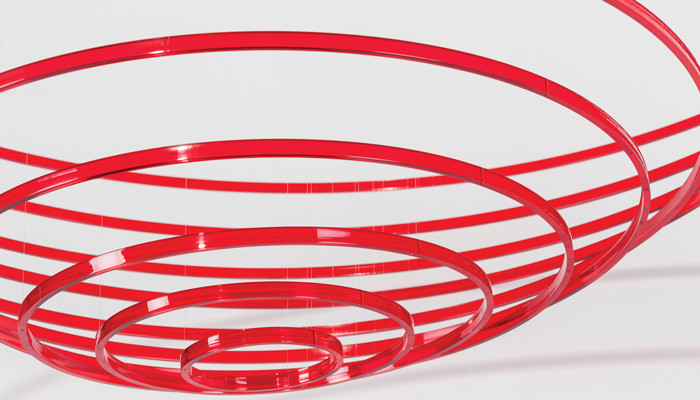

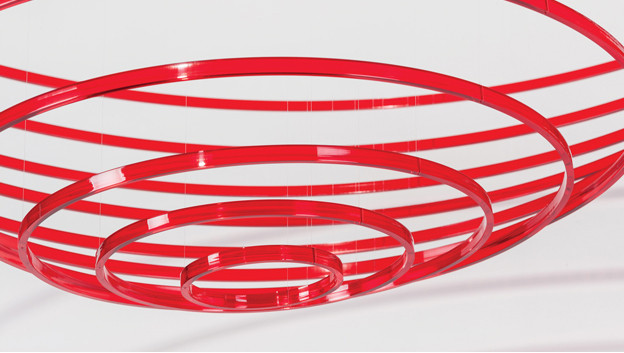

Later, the development of the abstract geometric current in the Global South brought about an alphabet of forms, elements and basic signs to include allusions to cosmic manifestations and stellar systems. And with confidence in its transforming potential on mankind and his social entourage, a good part of concrete, historical art developed an attraction for the concept of motion, pervading the establishment of a ludic relationship with the spectator. During the 60´s, an entire generation of artists developed a new vision, deeply aligned with the spirit of the first moon landing. Concurrently, the period saw the development of kinetic art, which would have transcendent repercussions in Latin America. In fact, the conception of the work as a perceptive and sensorial event activated by virtual, mechanical, electric or atmospheric means, requiring the spectator’s participation, possesses not only a ludic component, but also often its idea of motion metaphorically alludes to cosmic dynamics and astral displacements.

Likewise, the cosmic aspiration of the global South can be staged by resorting to spiral or concentric structures that emule —sometimes with sophisticated electronic means—the orbital motion of the planets. Like the ancient Mayas, contemporary artists endeavor to transcribe what is written in the sky and in the enigmatic human heart.