PAST EXHIBITION

Revision: Angel Delgado

Curated by Aluna Curatorial Collective

Aluna Art Foundation inaugurates a new headquarter in Little Havana, Miami, on April 18th of 2015, conceived as a space for art and culture to generate new dynamics in the sector and in the city.

The inauguration will take place with the release of several exhibitions dedicated to the concept of Parrhesia, a term which in ancient Greek meant “speak the truth,”- and the contradictions between censorship and the exercise of freedom of thought in artistic creation and literary. “In Parrhesia -defines Michel Foucault-, the speaker uses his freedom and chooses frankness instead of persuasion; the truth instead of falsehood or silence; the risk of death instead of life and security; criticism instead of flattery; and moral duty instead of self-interest and moral apathy.”

In the Room A of the new space, Aluna Curatorial Collective presents “Revision: Angel Delgado”, the first exhibition that centers around truth and censorship, and the first solo show in Miami by this Cuban artist, who at 24 years of age was sent to prison for an act of artistic contempt on May 10, 1990. The critic, Rachel Weiss believes that on that day “the nineties in Cuban art metaphorically began.” This exemplary punishment worked, according to critic Andrés Isaac Santana, “as a warning to other creators” and led to a “certain cynicism, consecrated as an strategic and aesthetic posture of survival in the island”.

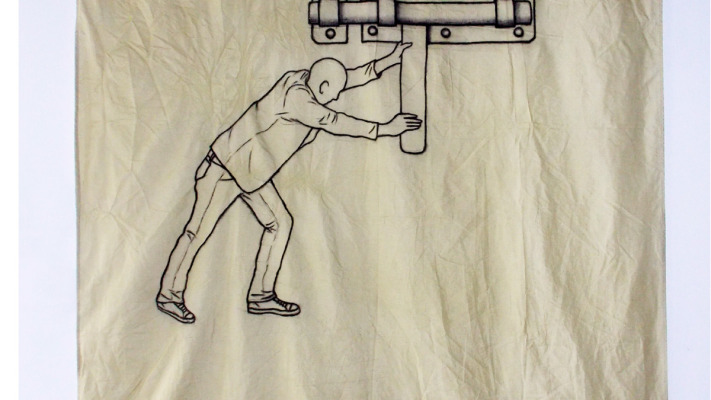

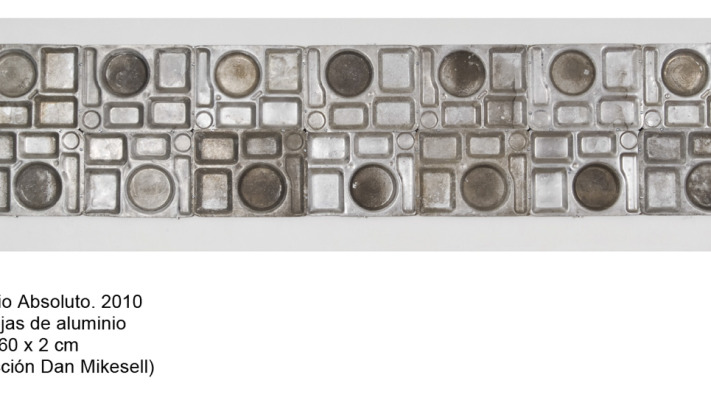

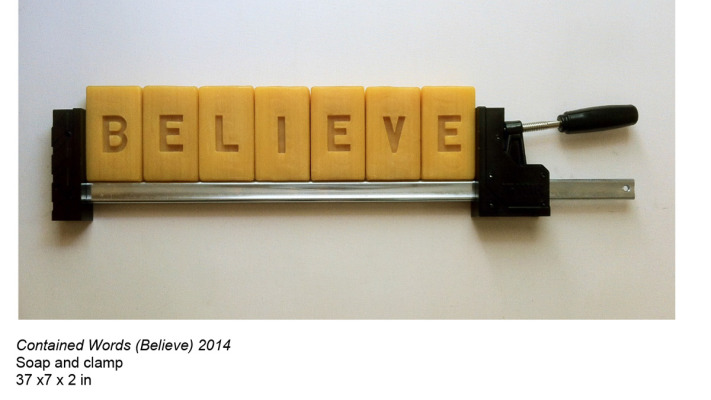

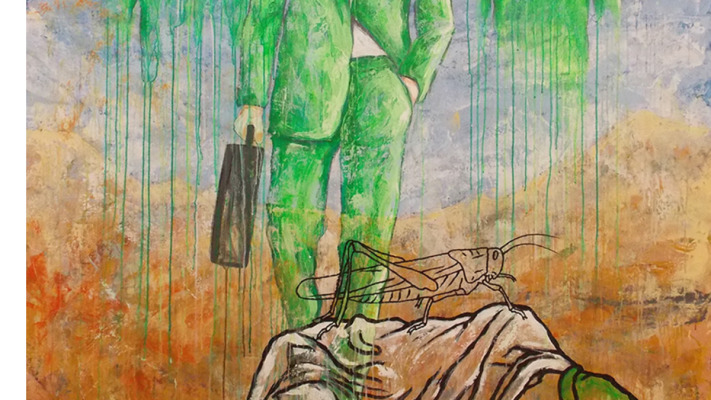

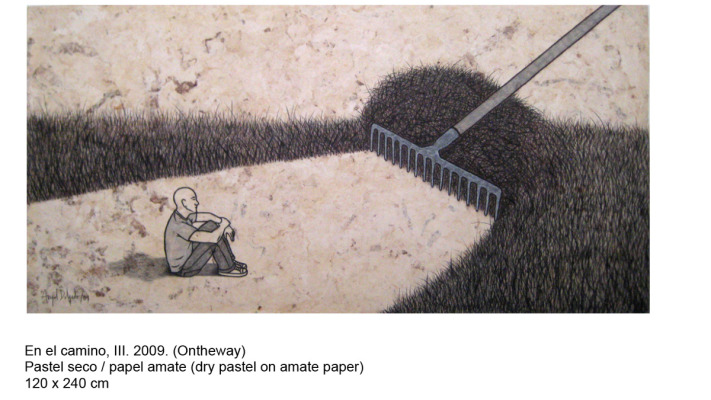

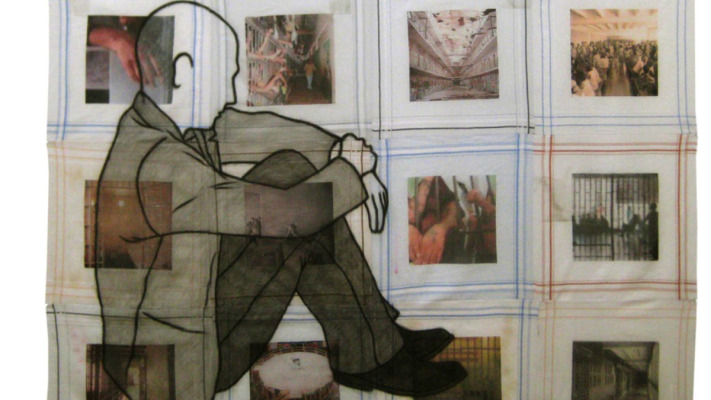

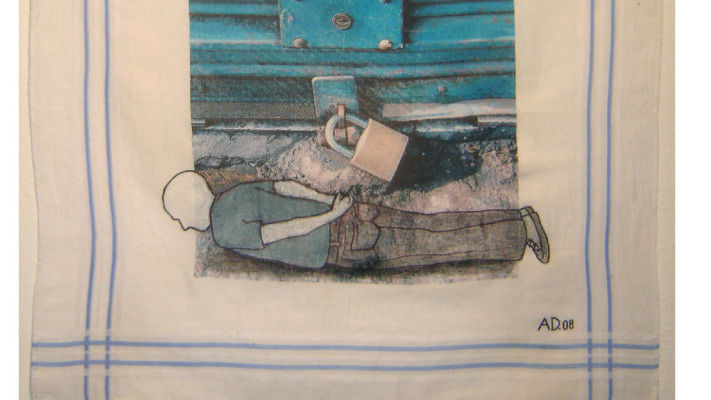

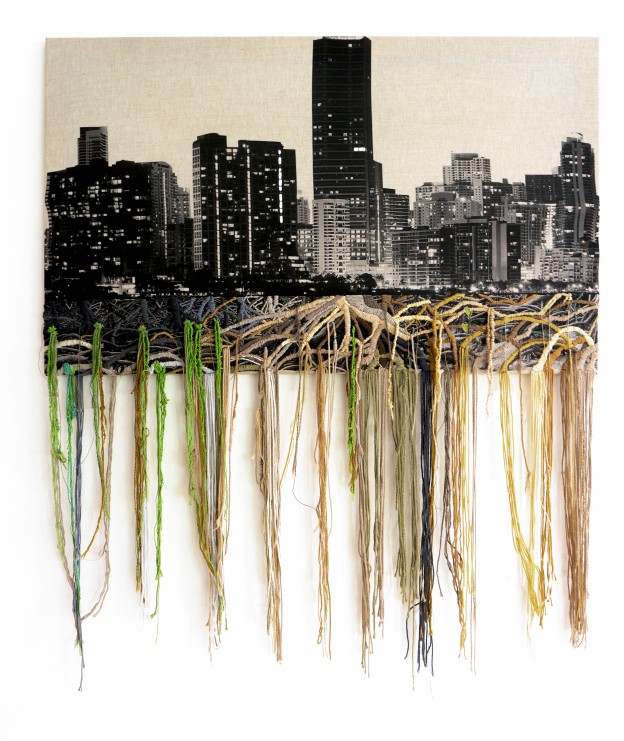

Delgado, whose work was deeply marked by this experience, preferred not to title his exhibition with the term “Parrhesia” or to say truth above all else because he’d be lying if he said that his work done in Nevada, where he lives today, would bring danger. “Revision” incorporates sculptures and drawings from the last decade, with media such as soaps, trays or sheets derived from the practices of survival from prison. It also presents serigraphs inspired by an alphabet invented then and large paintings about forms of oppression in a dizzying and globalized world but corroded social indifference.

ANGEL DELGADO: REVISION AND RESISTENCE

By Aluna Curatorial Collective

The work of Angel Delgado (Cuba, 1965) is a continuous endurance exercise, a form of resistance. In Latin, the verb resistere is equivalent to standing firm, persisting, and is composed of two terms: “re” meaning intensified action, repetition or backtracking, and the verb “sistere” derived from “stare”: to be standing. That was the internal exercise that he was forced to do during the six months he faced in prison when he was 24 years old. The sentence given for the crime of public scandal attributed to his situationist-like performance La esperanza es lo que último que se está perdiendo (Hope is the Last Thing we are Lossing) was the ultimate expression of surveillance and punishment in a system whose explicit and disciplinary cultural policy radically refused anything “outside (the revolution)” and advocated that ” everything ” should be confined ” within it.” But it is also the artistic practice that he has repeatedly maintained within the limits of material means –sheets, scarves, intervened soaps— transplanted from inside the prison to the outside of contemporary art, rewriting the alphabet that he invented to liberate himself, or doing performances with which he goes back to prove that his ability to resist has not become lethargic: to imprisonment, to the soapy surfaces of the world, and to the multiple modes of confinement.

Each synonym attributed to the verb “resist”: to bear, endure, withstand, last, stand, support, fight, oppose, cheer, stand firm, is a window into the body of a work that emerged in the barest frontier of fear as an act of survival but that eventually constitutes a conscious wager on the invisible boundaries of collective realities, a way to contend with the body itself—and with the social body— and to ensure that the possibility of remaining on one’s feet is intact. His art consists of inserting his own codes into the outside world hence expanding his space of freedom. He opens windows so we can understand that within the faceless urban crowds[1] there are also invisible powers at play like the flow of omnipotent capital that reduce us to numbers, equivalent to the 1242900 which was his identity in prison. The individual who was once under review in the different areas of confinement now examines reality, watches it closely, defies its limits, gropes its walls looking for fissures, and even notices the presence of a confinement in which other may not see anything. Those invisible walls of modes of economic control —i.e. the confinements of class in a time dominated by what Ben Davis calls “egoseus” (in an ironic play on the word museum)— are codes of coexistence that refer to other types of prisons.

The term “review,” chosen as the title of this exhibition by Angel Delgado, encompasses the reiterative insistence of the use of visual tools and the intervention of materials, both aesthetic practices learned during his time on “the inside” along with the codes of living; moreover the fact that he uses that set of learning tools to critically observe “the outside” of his own time. There is a continuous transposition of the space of prisions and the exterior world that makes borders between them explode —present in the handkerchiefs and sheets used and intervened with photographs of prisons and/or drawings, in the sculptures carved out of soap, and in the paintings with aerial views of panoptics. Prison figures refer to the claustrophobia of all worlds —including that of contemporary art— where the logic of transnational capitalism that does not obey any limit on its cumulative greed that turns pedestrians into ghosts unaware of their condition.

The criminal act of his performance in 1990, irrupting into the room that exhibited the participating works of “The Sculptured Object,” placing cardboards in a circle with the engraving of a green bone,extending the pages of the official newspaper Granma, and defecating in a hole of the center, at the moment expressed the collective unease of the growing atmosphere of public censorship of artists. That May 4th, 1990 marked, according to Rachel Weiss, the metaphorical beginning of the decade. “No one tried to prevent the excess” confessed Gerardo Mosquera, when in 1996 he wrote the text for the exhibition catalog in Espacio Aglutinador, where the curators Sandra Ceballos and Ezequiel Suarez made an installation with residual objects of his time in prison. Meanwhile, in Nosotros los más infieles (We the Biggest Infidels) Andrés Isaac Santana raises the need of rewriting the History of Art of the 90s in Cuba to address how this shameful confinement marked “a change in the modulation and in the conception of the aesthetic discourses, and the advent of cynicism consecrated as a strategic and an aesthetic posture of survival on the island on the damned circumstance of double standards everywhere”[2].

Delgado declined to use, as a title to this exhibition in Aluna Art Foundation, held on the 25th anniversary of his incarceration, the name of Parrhesia (the Greek term that stands for “truth” at the risk of everything), that our curatorial collective had proposed to him because it was the first exhibition in the cycle dedicated to the theme of censorship and truth. His decision was based on the fact that the works included were made in the last decade, covering this period of creation outside the island, both in Mexico and the United States. But if the power of his language comes from a continual return to the archeology of media and materials used by prisoners —not only in Cuba but in the global prison system—, it is no less true that the aesthetic of imprisonment modulates their way of expressing truth by transferring them to the outside world where the presence of freedom is eerie, like some the silhouettes of his paintings, and where other oppressions lurk. In fact, Granma is not the only newspaper that he has mocked[3]: During his performance “Digesting the News”, that took place in Mexico, he made a smoothie using water and various types of sweeteners, that he blended with sections of local newspapers. There was no lack of people who risked trying the disgusting drink.

Delgado does not risk any danger by telling the truth, however he maintains an almost obsessive exercise of resistance to multiple forms of coercion —to the sentences and the more subtle prisons—, and has constructed his practice by holding the vision of an invisible cell on his shoulders so as to not become lethargic, so as not to not forget to think of those big terms — truth and freedom— which when assumed from within, as a sharp cry pronounced by the mind and the body, are an act of resilience. He never forgets that when his time in prison was up, he left at midnight and found himself on an extended field under the moonlight, all the did as to run and run and scream. “The feeling of being able to scream is something you cannot understand until extreme things happen to you,” he says. The works in various media can be read as a sign of that inner practice of resistance associated with the truth. It is as if he echoed the words of Michael Payne: “We regret the eclipse of the truth.” In a conversation held with Christopher Norris, which gave rise to the chapter “Truth After the Theory,”[4] Norris refers to things that we perceive but that can only be known in their essential nature through an internal process of seeking-after-truth. This is the concept of truth as aletheia, as the moment of epiphany, of inward ‘unveiling’.” Delgado owes that moment of vision to his time spent in prison, which also generated the practice of resistance, as a continuous reality check, while he himself was being kept under surveillance. The proof of this are the papers he filled out, in the of a drawn diary, with an invented alphabet, in order to open a gap between the walls. If, as Wittgenstein argued, the limits of our language are the limits of our world, this exercise consisted in an invention, which could encrypt and expand his life experience safely. For the first time, the codes of the alphabet will be displayed as an inscription on a wall of the exhibition, which begins with a series of recent silkscreens formed from that act of liberating writing.

This set of private signs, objects made as an archeology of imprisonment, and the performances with which he examines once again his resilience to it, are also equivalent to the continuous construction of an indoor shelter that works like a “home” that he takes it with him from country to country. As it housted his spiritual and artistic obsessions it evokes to us the meaning of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau. Delgado’s invisible house is the consciousness of the panopticon that stalks, and whose limits, like the Möbius strip, are flexible: the outside and the inside occupy the relative place of the top and bottom, are established conventions for the transit of vision. Most of his practice is the continued resistance and the construction of this subjective refuge.

That is why “Revision” also includes photographs that document moments of intensified actions of his performances, where he enacts the dual function of resistance-shelter. Angel Delgado has been covered with a cloth and wires in a public place; he has been carried while immobilized by ropes to the sea or to an interior where he has remained tied for some time; and he has been incased in clay a fetal position, or he has been completely buried underground. He has learned to remain unchanged within the limits of extreme confinement so that within that practice of resistance he has found an inner refuge: his Merzbau.

His Paisajes incómodos (Uncomfortable Landscapes) speak of the invisible expansion of the panoptic, while the series Historias paralelas (Parallel Stories) dares to revive the genre of a type of social painting but emphasizing ontological questions regarding the course of humanity. In the painting we chose from this latest series, the parallelism is established between the comfort of an confident executive and the figure of a snail as a metaphor of those who carry their house on their back, and also as the double of the artist who travels as a nomad with the vision of an invisible panoptic on his back. In his iconic sculpture Hacia dónde vamos, (Where do we Go), an executive briefcase containing a herd of sheep —made of soap— that are marching in the same direction, while one or two (also the artist’s alter egos), go against the current. Ángel Delgado continuously carves out passages interpelling reality, stalking sites, mementos with the material remains of confinement but, above all, he takes on life as a work in which he finds refuge and bears the truth of his exercise in resistance.

[1] In his video “Three Minutes of Silence”, he filmed the wandering steps in a still shot. Gradually, the road dust reddens parallel to the moment in which the steps go backwards, in an incessant return, before a sweeper erases all traces.

[2] He was reinterpreting the famous sentence of the Cuban author Virgilio Piñera: “La maldita circunstancia del agua por todas partes” (The damned circumstance of water everywhere.)

[3] Delgado recognizes that during his trial he tried to erase the political implications of his performance.

[4] In the book written by John Schad “Life after Theory”, Payne addresses the consequences of the postmodern deconstruction of the concept of truth.