Exhibition Focus: Raúl Cañibano: The Island Re-Portrayed (1992-2012) | Cuban Art News, March, 2014

Published: March 21, 2013

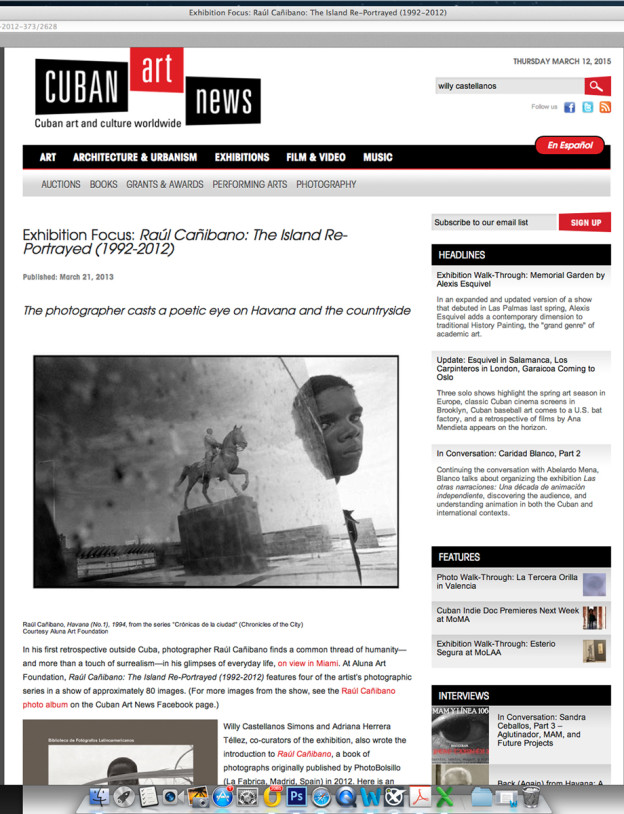

The photographer casts a poetic eye on Havana and the countryside

In his first retrospective outside Cuba, photographer Raúl Cañibano finds a common thread of humanity—and more than a touch of surrealism—in his glimpses of everyday life, on view in Miami. At Aluna Art Foundation, Raúl Cañibano: The Island Re-Portrayed (1992-2012) features four of the artist’s photographic series in a show of approximately 80 images. (For more images from the show, see the Raúl Cañibano photo album on the Cuban Art News Facebook page.)

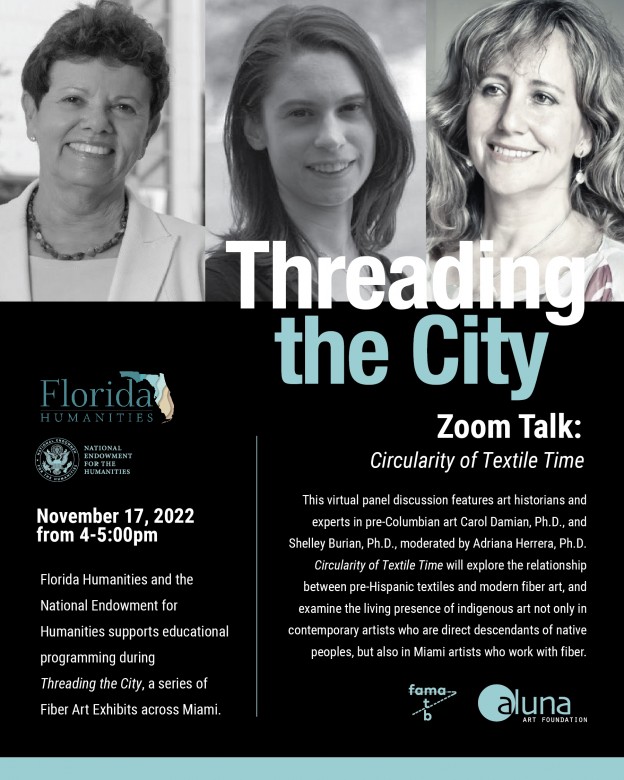

Willy Castellanos Simons and Adriana Herrera Téllez, co-curators of the exhibition, also wrote the introduction to Raúl Cañibano, a book of photographs originally published by PhotoBolsillo (La Fabrica, Madrid, Spain) in 2012. Here is an adaptation of their essay, abridged for length, in its original translation by David Alan Prescott, also titled “The Island Re-portrayed.”

The Island Re-Portrayed

Raúl Cañibano immerses us in the waters of the human in such a manner that he makes us live out that poem by Nicolás Guillén that exclaims: “Look at the street. How can you be so indifferent to that great river of bones, that great river of dreams, that great river of blood, that great river?”

In his long journey as a documentary photographer through the streets of that Havana that is deteriorated yet intact in its fascinating vitality, or into the island and its fields populated with amazement, his gaze has recovered a manner of representation that cannot be dissociated from the ontology of the Cuban; a knowledge that is as particular as it is universal of that great river of men of all time.

Cañibano’s gaze redefined the image of the common man through a complex documentary tradition, shifting the concept of reality towards areas that were not stamped with the heroic view of the person as a social being. His camera does not follow leaders nor emblematic figures, but rather anonymous people who go by in the streets, and the men and boys of the countryside whom he portrays with the stark complicity of the real. He accepts his position as a wanderer through the city and the journey to the countryside as a method, constructing a phenomenology of daily life in Cuba without metaphors, like an eye capable of capturing the extraordinary in the common instant and of at the same time creating an experience of nearness in the spectator. His series broaden the spectrum of the documentary image, recovering the infinite expressions of the individual relationship with the others, without distinguishing frontiers between public and private spaces.

The City of the Open Windows

There is an infinite quantity of references around the photographic representation of Havana. Cañibano is interested in its architecture as it dialogues with the human being. In his series “Chronicles of the city,” Havana emerges as the mirror of desires for the voyeuristic lens that follows the free wandering of the next person with its poetic charge: this is the Havana in times of leisure, where there are festivals, romance, rest and the gestures of socialization. He can catch them on the invisible stages of the street or indoors where he sometimes peers in by candlelight.

His wandering camera often prowls the coast of Havana and the walls that bound it: the omnipresent Malecón Oceanside walkway which is also a frontier of non-time, a space of unearthly times, of meetings and missed meetings, around which the scenes are multiplied and often tinged with that aura that made André Bretón, who was passing through the city, feel like he had entered surrealist territory.

Cañibano seeks repeated forms, creators of rhythms, right where daily life reaches a mode of intensity without myth. In that City of Columns the passage of time favours narratives in bulk. Havana is superb in its deterioration, and is generous to excess in decisive instants that the photographer steals from life. Taking advantage of the order of the coincidences, he creates parallels in scenes that are appetizers to multiple potential readings, uniting situations that may have a relationship of stating or of contradicting through the conceptual charge of the image. In this manner he reconstructs life – like Joyce did in his native Dublin – through a visual approach that captures the chaotic convergence of the urban experience using the simultaneous nature of dissimilar situations.

Cañibano’s gaze travels through the open city revealing its spaces, feeding off the histrionic feeling of the Cuban who, as the critic Juan Antonio Molina once said, gives himself with glee to the pose and the theatrical game. One loves Havana, although it is no longer like when Luis Cernuda saw it, “beautiful, aerial, airy, a mirroring”; and because for each Havana resident it is still the “city with most open windows,” as Abilio Estévez wrote in his Inventario secreto de La Habana; or, just as Fayad Jamis lived it: “This is perhaps the true centre of the world.”

Myth and Reality

Cañibano’s series “Ocaso” registers the overwhelming loneliness and abandoning of old age in Cuba, as a metonymy of the cracks in the system. These images taken in an institution or in the streets of the capital explore a facet that is not often shown but which was often visited by other documentary photographers of the nineties. Cañibano accepts the challenge of this rhetoric and constructs an emotive social document with a strong human impact.

Brimming with the elegance of visual maturity, “Ocaso” stands as a cognitive experience that works through catharsis. The series transcends the meaning of each initial shot, drawing out the tale of a world alienated by social indolence. It is a pessimistic view, but which brings out the exceptional value of the individual gestures that restate life in its unshakable dignity.

An analogous exploration of the drama takes place in “Fe por San Lázaro,” a series which delves into the survival of religious sentiment in Cuba. Every 17th of December thousands of devout worshippers congregate at the Rincón Hermitage, a few kilometers away from Santiago de Las Vegas, in order to form a penitent procession with one of their most revered figures: not Lazarus, the resurrected, but the beggar in the parable in St Luke, Babalu-Aye in the Afro-Cuban religion, lord and master of the contagious diseases and protector of the sick.

Photography as an Exercise in Socialization

One Hundred Years of Solitude, one of the most important books in Latin American literature, arises from the journey that took García Márquez, many years later, back to the land of his origin and to the desire of “leaving poetic constancy from the world of my childhood.” In a parallel manner, Cañibano felt the call of the “Tierra guajira” [Guajira Land] where he lived a part of his childhood in the Argelia Libre sugar mill in the town of Manatí, in the province of Las Tunas. “Tierra guajira” is inspired by that return, which is as geographical as it is affective, giving rise to the most lyrical of his series, and that which defines the journey as a resource, and photography as an exercise.

“Some were very difficult journeys,” he comments, “and on others I had the opportunity to strike up friendship with the peasants and stay in their houses for days, sharing their shortages (…). They are very noble people and they share what little they have. And I helped them bringing them work clothes and tools that I got in Havana. I thus travelled from town to town, first along the Martiana route, from Playita to Dios Ríos, and then all throughout the countryside: Gibara, Remedios, la Ciénaga, Consolación del Sur and La Isla de la Juventud.”

The series was carried out as a long term essay, and contains the poetics of an unbreakable alliance between the soil as the source of life, the man who works it and the animals that live on it. It is a stark gaze – just like life in the countryside – but one, which registers the sensitivity of the country peasant through his daily ritual activity, whether at work, at celebration, or in the intimacy of those homes with their doors always open.

Both the urban images and the rural ones are mainly taken of moments of leisure – that space ignored by the photography that preceded him. But while in the city one can sense an atmosphere of isolation and fragmentation, what predominates in the countryside is an inner unity that projects the imaginary of a pleasant world, without any ruptures. Thus the photographer’s simultaneous work on both series establishes a revealing counterpoint on the aesthetic and sociological level.

It is very possible that the photographs of the boys may function as self-portraits, in an attempt to bring back the marks of a childhood blurred in memory. In conspiring with his games, the photographer captures a playful power capable of bending reality, and recreates a particularly beautiful instance of his relationship with the animals, built on the certainty that the life of one realm is not possible without the other one. If “literature is childhood finally recovered,” as Georges Bataille states, Raúl Cañibano’s photography is the idyllic recovery of that “Tierra guajira” by means of a camera that looks at reality with the eyes of the child he was, and gives him back his innocence.

- Willy Castellanos Simons and Adriana Herrera Téllez

Raúl Cañibano: The Island Re-Portrayed (1992-2012) is on view through April 13 at Aluna Art Foundation in Miami. For additional images from the show, see the photo album on the Cuban Art News Facebook page.