Aluna Art Foundation enlivens the summer with an eclectic mix. The Miami New Times, 08.15.2012

By Carlos Suarez de Jesus

It’s safe to say that Billie Grace Lynn, a professor of sculpture at the University of Miami, won’t be lining up at the latest gourmet burger joint opening in South Beach.

“When it comes to how we use and abuse animals, we are ethically and morally bankrupt,” the artist declares. “They are conscious beings who feel love and fear. We are paying, even now, a huge price for our crimes against them.”

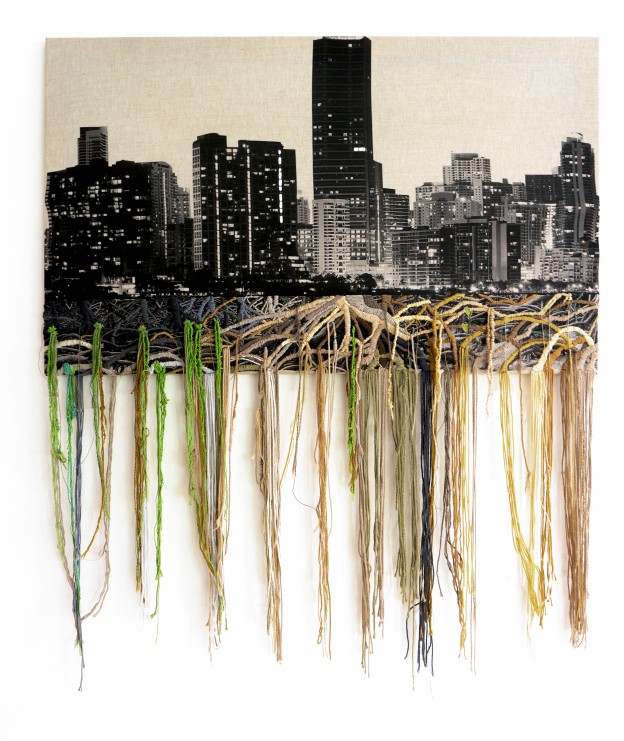

The sculptor is so passionate about animal rights that her latest project is a paean to the inhumane treatment of farm animals. If that sounds a bit preachy, consider the form of her protest: a diesel-fueled motorcycle made from a full cow skeleton. And consider what she’s doing with it: plotting a road tour of the country in a modern version of Easy Rider.

A photo of that bony bike, part of Lynn’s ongoing Mad Cow project, is among the works featured at the freshly hatched Aluna Art Foundation in downtown Miami, where the new gallery is devoted to local art outside the mainstream. On August 25, she’ll show off the work as part a performance staged in conjunction with the center’s inaugural exhibit, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” on view beginning this weekend.

It’s one of several exhibits opening around town later this month to enliven the last few weeks of Miami’s traditionally sleepy summer season, including a schizophrenic ode to Marilyn Monroe.

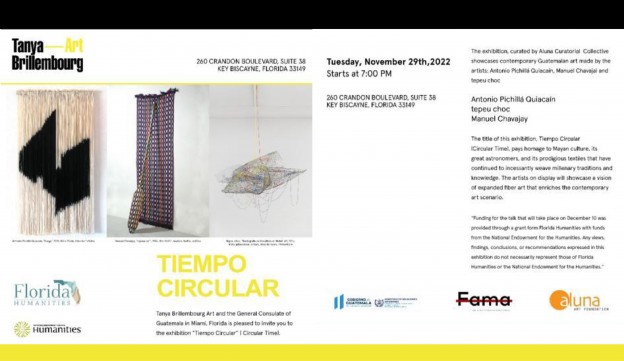

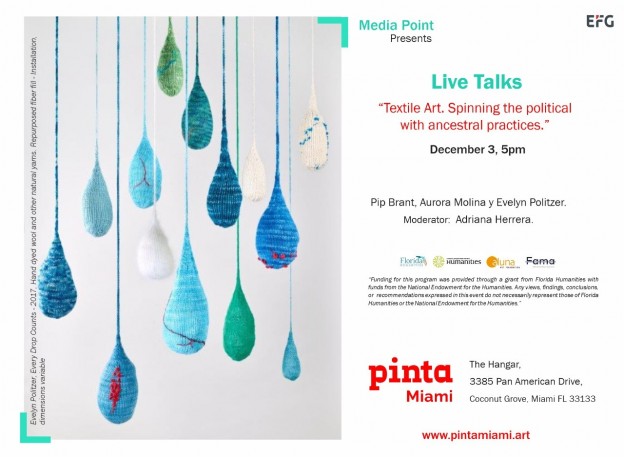

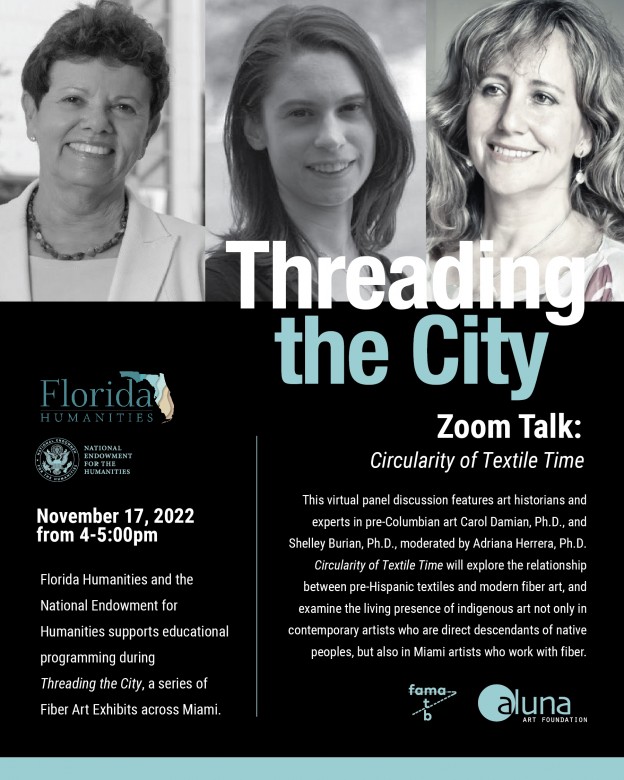

“Our mission is to showcase artists who are underrepresented,” Adriana Herrera, the gallery’s curator, says. “Our goal is to create an ongoing dialogue with lectures, panels, and artist talks and to bring emerging and established voices together.”

Lynn’s work is among the highlights of the new gallery’s first show. Her latest motorcycle project came after she won the West Prize for an earlier, electric-powered version of the bike. The artist’s kinetic sculpture was chosen by the West Collection, a private collection based in Pennsylvania, from thousands of global applicants.

Lynn, who is 50 and grew up near a cattle farm in rural Louisiana, used the prize money to create the fuel-efficient diesel model. In preparation for her maiden voyage, her performance at Aluna will touch on themes of environmental degradation.

In the gallery, she’ll be surrounded by scattered cow skeletons and video projections of slaughterhouses, wars, and industrial pollution to re-create a charnel-ground vibe. She’ll sit on a milking stool while spectators are invited to take turns helping shave her noggin and placing her shorn tresses on an altar for use in later works.

“Through the loss of my hair, I am trying to express my desperate feelings of loss, fear, and pain,” she says. “I am hoping that we shall change our ways before it is too late.”

Lynn’s confrontational work fits Aluna’s larger mission — to feature artists who don’t easily fit in the mainstream Miami art scene. Founded by art historian Guillermo “Willy” Castellanos and Herrera, who is also an El Nuevo Herald art critic, the foundation takes its name from a word used by Colombia’s indigenous Kogui people meaning “a state of vast potential before becoming manifest.” Castellanos and Herrera, co-curators of the exhibit, hope to create an ongoing dialogue about the evolving nature of contemporary art.

“Visitors will discover that all of these shows and the artists involved are linked by a search for transcendence and the spiritual in their own unique way,” Herrera says.

That includes the gallery’s inaugural group exhibit in the main space, which features an eclectic collection from a pan-Latin group of artists including Venezuela’s Andrés Michelena, Evelyn Valdirio, and Lili (Ana) González; Cuba’s Heriberto Mora and Raimundo Travieso; Colombia’s Jorge Cavalier and Sara Modiano; and Argentina’s Nicolas Leiva.

Among the standouts are Cavalier’s arresting installations — featuring large-scale canvases and imposing labyrinthine cut-metal sculptures — which reference the primeval forest as a symbol of spiritual regeneration. Valdirio weighs in with haunting imagery of angels, while Michelena explores the cosmic void with a striking rendition of Buddha, and Mora adds a conceptually fresh approach to Virgin iconography.

Aluna also includes a space called Focus Locus, which houses photography and mechanically produced art. The first series on display, Cuban Prayers, is Gonzalo González’s collection of photographs of Havana exploring the cult of Cuba’s patron saint, La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, and celebrating the 400th anniversary since she became a key part of the island’s native faith.

“The Latin root of the word religion means to become reunited with a source of the infinite,” Herrera observes of the exhibits on display.

While Lynn’s visceral, shock-inducing approach might discomfit some visitors, it’s worth a trip to Aluna to witness the elegant, rarely displayed installation by Colombian talent Modiano, who died in 2010 at the age of 59.

Her simple, abstract wire-cube geometric construction, titled Being #4, hints at the stability of the material world while evoking the ethereal nature of the infinite.

If Aluna’s deliberately outsider aesthetic isn’t your cup of joe, the upscale Village of Merrick Park has a 180-degree antidote at Galleria Ca’ d’Oro, where the legend of Marilyn Monroe lives on 50 years after her death.