News

PABLO LEÓN DE LA BARRA OR CURATORSHIP AS LUDIC MANIFESTO

(Arte al Día International, Thursday, May 15, 2014)

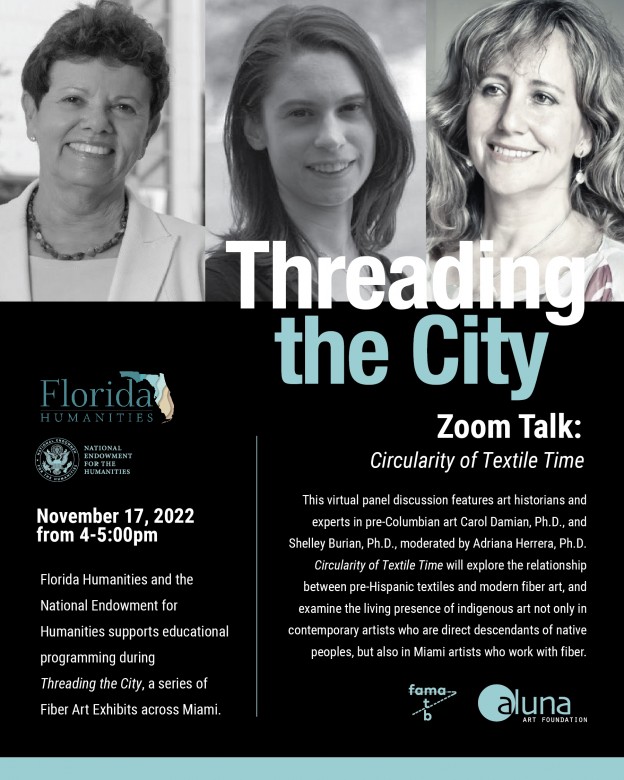

by Adriana Herrera Téllez

Playfulness –in its most genuine and lighter expression, yet one that is capable of shaking our world imaginaries – is, like the shadow of Pablo León de la Barra, the new Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative Curator of Latin American Art, inseparable from his figure. An invaluable advantage for the contemporary art of the region, which he will bring to the iconic New York museum during his two-year residency.

In his blog, Centre for the Aesthetic Revolution, there is a Jacques Rancière quote which has never been removed. Invoking Schiller’s thinking on how “man is only fully a human being when he plays”, the theoretician half-opens the horizon of an aesthetics that holds the promise of “a new world of art and a new life for individuals and the community”. The potential of this promise might well define many of León de la Barra’s curatorial endeavors. In each curatorship there is an unusual playfulness. It contains, on the one hand, a contempt for the established (including the hierarchies of artistic fame), and on the other, a lucid form of attention to people in the environment where artistic practices are carried out or displayed.

It is unusual to find somebody who knows how to avoid the coupling between the freshness of intelligence and reluctance to power; someone who can watch with tireless surprise the gestation of art in any place, while betting on the unknown. Pablo makes generosity a relational practice that generates a continual nomadism, a characteristic that allows him to simultaneously detach himself and take root in the changing spaces where he radiates his creative joy. His way of becoming involved is equivalent to exercising the tenderness required to see and pulsate the less visible spaces of culture. As was the case with Julio Cortázar –with whose gigantic child’s playful spirit he has so much affinity– not loving Pablo León de la Barra seems impossible.

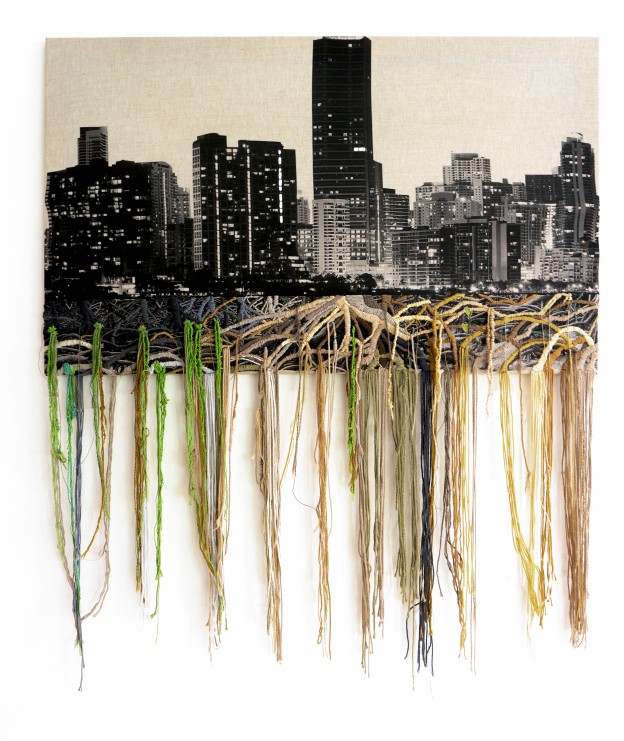

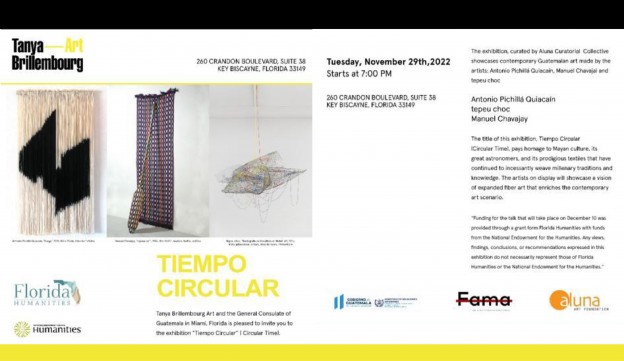

I meet him in New York to continue with a conversation held in bits and pieces in different cities and years, intersected by ubiquitous images. I recall the skin of a banana plant, a work by Adriana Lara that I saw at MACO, in Mexico, which was later documented in TeorÉtica, Costa Rica, as a missing piece –against his wish– on the occasion of the launching of the Novo Museo Tropical project. He forged this “museum without walls” to subvert the exotic framework of Latin American ‘banana’ art by means of “a historiographical chart shaped like a banana bunch” that brings together in that stereotyped image “artists, artworks, avant-garde movements that are part of the artistic and visual field of Latin America.” A mobile museum that distorts the very clichés of the tropical to narrate stories against the current of the socio-political marginalization in the continent. I evoke Teresa Serrano’s performances, Milagro de la Torre’s photographs of sophisticated bulletproof suits and vests, and the work by Manuela Viera-Gallo that I saw at Pinta New York 2010, years after Pablo had been forced to move from the neighborhood where he lived in London precisely on account of an installation by this artist featuring a pair of huge pink panties. It was shown on the wall of the building where Pablo lived –and where the flagrant Colombian-London flag devised by Carolina Caycedo had already been hung. After these public art interventions –which he conceived together with Sebastián Ramírez and Beatriz López (currently the director of La Central gallery in Bogotá) as a strategy for 24/7 gallery, which operated in the street for artists who were not from the city and had no venues in which to show their work, they began to stage exhibitions in the bathroom of the London pub The George & Dragon. From being an assiduous visitor at the pub where Ramírez and López worked, Pablo had gone on to run it and to devise in 2003 the iconoclastic White Cube Toilet Gallery (so similar to the name of the established gallery White Cube), which continues to demonstrate that it was a wise decision to experiment in micro-spaces.

I also visualize the hammocks which were hung along the sidewalks of the cold Bogotá city, Colombia, by the Public Space Interventions Office, which had issued the invitation to participate in La Otra Contemporary Art Fair. Or the rainbow made from plastic tubes in the tropical garden designed by Radamés “Juni” Figueroa for his curatorial work for Somewhere over the Rainbow at the Circa Labs in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where Stefan Benchoam, of Ultraviolet Projects, sold pirate copies of video or film artists (I still have Theo Jansen and Chris Burden, among others). But it would be an endless task to trace the map of itineraries and works with which Pablo has put institutional limits at stake, or investigated architectures on the border of Latin America’s disorder, in those popular aesthetics of large cities that he has evoked as another mirror of obscenity and misery, although also of the beauty of chaos. But he has done so without idealizations. In some Latin American street he shot, in 2003, a graffito which read “Solitude”.

I enter the Guggenheim with Pablo. We stop at the rotunda where people lie down, immersed in the color atmospheres that the changing natural and artificial lights of James Turrell’s first exhibition in a New York museum since 1980 emanate. He explains to me the fantastic architectural transformations that filled with curves the space designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and he shows me the peripheral wing that will host the exhibitions of Latin American art of which he will be responsible. Impossible not to evoke Carlos Cruz-Diez’s chromosaturations, but besides, he confesses that in that conjunction of light, radiated color, space, and perception, he cannot help evoking Luis Barragán. In the 1990s, he shared with other students from the School of Architecture of the Ibero-American University –like Pedro Reyes and Tatiana Bilbao, or Fernando Romero– a renewing obsession for his work. They sort of worshiped him in clandestine events that they held in closed buildings such as the Tower of Winds. They belonged to a generation that was searching for its identity in the void of the mirage of vanished modernity, and felt as palpable this other experience of light that Barragán created within stone walls, in the midst of the eager desire for a creative freedom. Having just graduated in Architecture in the Federal District, Pablo undertook an internship as assistant to the director of Barragán’s house-museum. He spent time following its shadows and reflections, inhabiting the space. He walked with his shoes off, eyes closed, smelling and touching materials in order to feel and understand.

Before he traveled to London in 1997 to obtain a Ph.D. in Architectural Design and Urban Planning, León de la Barra practiced an unruly architecture. He built on abandoned lots. He intervened in an industrial area in order that the space might be re-used as a school. But on the very border of a mode of social practice, he wondered whether ruins should not be left as such. Already at that time he immersed himself in –and confronted– the writings of María Zambrano or the work of Félix González Torres, and works that adjusted to his own canons, like those of Helen Escobedo and Marcos Kurtycz or Felipe Ehrenberg, or simply tableaus, pieces or performances in which he recognized the energy of genuine creation.

To talk about his training as a curator-cultural agent, one would have to mention such dissimilar experiences as witnessing the work of the Canadian artist collective General Idea, founded by AA Bronson, well-known for his secrete performances in secret locations –a little like those now-forgotten ones staged by León de la Barra with his friends– and by Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal. The group dissolved in 1994, when the two latter died of AIDS, precisely one of the key themes in their installations in public places or in the works that “infiltrated” forms and spaces of popular culture. But he was also marked by his trip to India in 1999; there he found “another Mexico to the nth degree”, alphabets of a language and an aesthetic of the crisis characterized by an informal culture. His photographs of large Latin American cities capture reflections of the broken surfaces of modernist mirages, as traces of an ongoing research which gradually led him to conceive each exhibition as an investigation of that which, in the absence of a better name, we term Latin America. Once he finished his Ph.D. in London, he obsessively turned “his eyes to the south”.

An early curatorship developed as a social inquiry resorting to artistic tools and generating exhibition spaces was the one he carried out for The Artist as an Ethnographer: Museo del Cerro de Naranjito, 2002, held in that shanty-town sector in Puerto Rico, where Chemi Rosado painted, with the help of the people, all the houses in different shades of green, generating a different social landscape, a type of work that went from representation to action.” Pablo visited the houses in the sector asking the people to lend him objects for the staging of an exhibition in a community hall reinvented as a museum.

Meeting the curator María Inés Rodríguez was a decisive event. They met in Paris when Pablo was participating in an exhibition of young Mexican architects. “I was attracted by his vision of the city and the way in which he showed it: a series of slides featuring typologies of Mexican modernism projected in a simple setting that included two Acapulco chairs and a color carpet…”, says Rodríguez, who invited him to work in an itinerant project between Paris and Bogotá, marked by the idea of thinking art in terms of the corresponding city, and of including in this art the thought of inhabited space, and making access to this space possible for those who did not have access to it.

In Brasilia, Pablo had seen a beggar, José Ivanildo, asking for alms in the streets in order to fulfill his “Dream of a house of one’s own.” They fostered his dream through the exhibition co-curated by Ivanildo and Rodríguez that bore the mentioned title and inquired into aesthetic formulas imagined by artists, designers, and architects such as the collective Tercerunquinto, Raúl Cárdenas, Yona Friedman and Santiago Cirugeda, among others, to solve the housing problem.

The manifesto that accompanied –as an itinerary tool– his exhibition To Be Political it Has to Look Nice: How to be a Proper Latin American Artist (A Guide for Survival in the Global Cultural Economy), 2003, presented at NY APEX ART on an invitation from Carlos Basualdo, is still valid a decade later. His exhibitions function as devices to investigate the cultural articulations between the aesthetic, the political and the social aspects that occur or manifest themselves in that part of the continent which he would have preferred to define, like Los Prisioneros, saying that we are “South American Rockers”.

In De la Barra’s exhibitions there is an “architecture” that expands the white cube in multiple ways – he can mount it anywhere, make it mobile or disguise it, or fill it with non-artistic objects not chosen with Duchampian indifference but having a local emotional charge and ultimately reconnecting art to personal life and to the social world. They operate, in turn, like certain Borgesian dreams, like an exhibition inside an exhibition inside another exhibition, but they tend to produce some sort of awakening to social realities. An awakening that is enhanced through the social networks that Pablo León de la Barra electrifies and reinforces with his lucid joyfulness.

In the museum´s cafeteria he asks the cashier about her origin and takes time to listen to her. Then he attends a homage meeting with the museum’s executives, where he will be faced with the huge challenge of thinking, once again, the implications for art of the definition under construction of ‘Latin American’. A notion to which he incorporates untold stories –which were not part of the official records of art, especially during the decades of dictatorial governments–, and the creation of new maps, as well as humor to deal with reality, and the dialogue between the particularities and differences that exist in the countries of the Continent, independently of their common history; all of them key elements to inquire into the less visible. On our way out, I take a picture of him standing between the entrance to the iconic museum and a hot-dog cart. The photograph is not good, but watching his tall, smiling figure I think that he will always be in that interstitial space, that he will never stop having one foot on the streets where the river of people flows in all the large cities of the world.