Milton Becerra: “Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz”

By Adriana Herrera Téllez, Ph.D.

(Essay for the exhibition catalog | Art Nouveau Gallery, Miami. November 2014)

Milton Becerra, time traveler and explorer of vast territories, interweaves in his art forms derived from spatial-temporal sources which, being as diverse as they are distant, converge in a same revelation: they reflect the prodigious fabric of the universe. Thus, he bridges the gap between America’s past and the discoveries of quantic physic theories, and the first tools of prehistoric times and his geometric abstract contemporary sculptures.

If for someone like Jesús Soto, abstraction had to be “pure structure”, and seeking that purity, he brought form closer to music, Becerra takes another path: without denying the representation of the world, he seeks to reflect in his work a representational system that recalls the sense of play that animates creation, and the inaudible music contained in the interrelation of all elements.

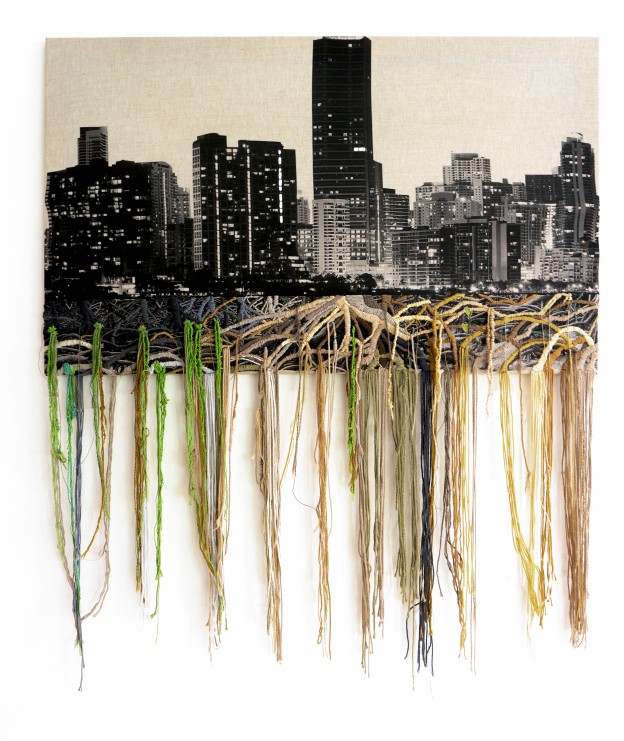

Milton Becerra is of indigenous descent and he has completed a long journey that culminates in the works that make up the exhibition “Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz”, at Art Nouveau gallery. In these pieces, geometric forms –regular or irregular– function as supports for ludic looms. The tautened color threads create superimposed warps that allow an infinite perceptive variation, depending on the intensity of the light that falls upon them, on the angle that lights them up, as well as on the gaze of the spectator and his/her position in movement.

In relation to the loom, we know that countless people have used warps with lukewarm threads to achieve the tension required to weave those fabrics that served to create clothes, as well as to produce sacred canvases on which they drew the myths associated with their origin or the stories about their journeys. Milton Becerra builds his contemporary sculptures as unique looms, with a free play of combinations and irradiations between the color and the shape of the frame, and between those of the threads that function as superimposed wefts and project before our eyes in movement kaleidoscopes of amazing geometries.

His creative thought was therefore initially molded by the contemplation of the river rocks on which the Pre-Columbian peoples inscribed the geometric forms of their myths, and by the oral traditions that record them. He grew up in Las Delicias, a town on the banks of the Táchira river, in Northwestern Venezuela, listening to the language of the water on the stones, but his memory only recovered them when he arrived in Paris to live there in the 1980s and began to use them as an alphabet to build his own universe, with an awareness that returned him to the origin, to the knowledge that everything is written on the stones that do not only lie on the river beds but also float in the course of the heavens.

The mythic Wale’kerü spider that appears in the title of this exhibition taught the art of weaving to the Wayúu people, the native inhabitants of a territory that stretches along the border between Colombia and Venezuela, and Milton Becerra, with his abyssal curiosity, resumes its spinning and links it to the understanding that the entire universe is a fabric of luminous cords that vibrate in a way that manifests itself in diverse material forms. For this reason, in his structures there is an echo of those models of quantum physics that seek to harmonize the laws that rule the macrocosm –the movement of the stars, planets and galaxies– and the occurrences in the microcosm, which is equally infinite, in the interior of the smallest particles in creation.

It was in the City of Light, which is currently one of the places where he lives, that he first combined rocks and cords in an installation he exhibited at the entrance of the 11th Paris Biennial, as an invocation to nature, the primordial source which also gives rise to the nests and labyrinths in his work, always tautened or structured with threads.

The Renaissance is also included among the hypertextual allusions that may be found in the pieces exhibited in Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz. It has received the legacy of the mathematician and artist Paolo Uccello, who as Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) narrates, was obsessed with the vanishing point and sought perfection in perspective, not to narrate stories, like his contemporaries did, but to represent the maximum dimension of depth. Even more than the famous mosaic by Uccello on the floor of Saint Mark’s Square in Venice, and in which the hexagonal prisms crossed by a cord suggest the three-dimensional through perspective and colors, what interests Becerra is the mazzocchio that Uccello painted many times and Leonardo drew: “In that first modular spatial structure —reassures—, forms are repeated in such a way that it creates the maximum possible number of edges.” Repetition, depth, and the sum of edges projected ad infinitum and highlighted by color alternation –light, dark, like a chess board– are key aspects in his works. It must be recalled that the mazzocchio was incorporated in a type of Renaissance fabric –intarsia– and of works in wood in which colors function as linked pieces but are independent, as a kind of jigsaw puzzle.

Of course, it is also unavoidable to perceive in his compositions the knowledge of the formal findings of kineticism, and over all, of the inquiries into the nature of color radiated into space. But challenging the guiding principle of the great kinetic masters who sought to avoid all figurative references to the existing world, Milton Becerra’s installations and sculptures contain the apparent paradox of representing that which is invisible to our eyes: they reflect those behaviors of matter that we do not see because they occur at visual scales that escape our perception, but that are equivalent, however, to a sort of cordage of the universe.

In fact, the suggestive power of his vision artifacts –because in this aspect he coincides with Marcel Duchamp’s explorations– resides in that it appeals to the unconscious memory of humankind in a way that evokes the shapes of archetypal geometric patterns or those of universal tools such as the looms that date back to the Neolithic, but also the Renaissance plays with perspective and color and the models postulated in theoretical physics such as the theory of supercords, which explains that all physical fields and particles are modeled as vibrations of thin supersymmetric strings, moving in a space-time of more than four dimensions.

Actually, representation is in this case a multi-dimensional way of “painting” the fabric of the universe: instead of drawing lines on the plane, it tempers cords in space, evoking super-symmetry models and inducing in the spectator the experience of perceiving that forms are also vibrational states, radiations of energy. For this reason, in these three-dimensional works by Milton Becerra there are not only traces of techniques and myths associated to the memory of the millenary and juxtaposed looms, or incorporated lessons that contain the figures with which Uccello approached the grid of reality and the legacy of figures like Cruz-Diez or Soto; or of the models of the very echo of Quantic Physics: His works open up kinds of multidimensional geometric passages. The artist deposits in them a myriad of references, but above all the possibility of disseminating the energy they concentrate in the surrounding space through the changing shadows and the radiations of colors in ceaseless transformation over the course of the day.

“Weaving –he assures– is not a simple thing. The color threads, tautened to the maximum tension in these small contemporary sculptures, artifacts where visions are woven, produce vibrations wherever they may be.”

We are faced with multidimensional geometric works which, installed in a specific place, refer us to the world’s architecture, but also to the inner space. They function as transcendent objects: they connect us with the vision of a unity that is beyond the works themselves and that refer, if you will –to put it in a Platonic way– to the form of all forms.

Each space-time is transformed under the action of what the mythic Wale’kerü taught: to imitate the fabric of the universe using threads of light. Imbued with a powerful playfulness –which invites to engage in a visual play and even incites the sense of touch– from each of his sculptures there finally emerges a mode of contemplation that is very similar to the amazement out of which philosophy is born, and taking advantage of the trace of art histories ranging from Pre-Columbian to Renaissance art and from Geometric Abstraction to color field research, radiate an energy that is as changing as it is ludic. One must view them immersed in the play of lights and movements that surrounds them in order to listen to the inaudible sounds they contain, the celebration of the ceaseless birth of the forms they produce. What they ultimately reveal to us is synthesized in their statement: “Form exists because there’s a spirit.”

Milton Becerra: “Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz”

Milton Becerra, viajero del tiempo y de vastos territorios, entreteje en su arte formas provenientes de fuentes espacio-temporales que –siendo tan diversas como distantes– convergen en una misma revelación: reflejan el prodigioso entramado del universo. Así, acerca el pasado de América a los descubrimientos de las teorías de la física cuántica; y los mitos y las primeras herramientas de la prehistoria, a las esculturas del arte geométrico abstracto contemporáneo.

Si lo abstracto, para alguien como Jesús Soto, tenía que ser “estructura pura” y buscando esa pureza aproximó la forma a la música; Becerra toma otro sendero: sin negar la representación del mundo, busca reflejar en su obra un sistema de representación que nos recuerda el sentido del juego que anima la creación, y la música inaudible contenida en la interrelación de todos los elementos.

Milton Becerra tiene una línea de ascendencia indígena y ha cumplido una larga travesía para desembocar en las obras que conforman la exhibición “Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz”, en la galería Art Nouveau. En estas piezas, las formas geométricas –regulares o irregulares- funcionan como soporte de lúdicos telares. Los hilos tensados de colores crean urdimbres superpuestas que permiten una infinita variación perceptiva, dependiendo de la intensidad de la luz que cae sobre ellas, del ángulo que las ilumina, así como de la mirada y la posición en movimiento del espectador.

En relación con el telar, sabemos que incontables pueblos usaron las urdimbres con hilos templados para lograr la tensión requerida para las tramas de esos tejidos que sirvieron para crear vestiduras, así como para confeccionar telas sagradas donde dibujaban los mitos de su origen o las historias de sus travesías. Milton Becerra construye sus esculturas contemporáneas, como telares únicos, con un juego libre de combinaciones e irradiaciones entre el color y la forma del marco, y entre las de los hilos que funcionan como tramas superpuestas y proyectan, ante nuestra mirada en movimiento, caleidoscopios de asombrosas geometrías.

Su pensamiento creador fue así moldeado, inicialmente por la contemplación de las piedras en los ríos donde los pueblos precolombinos inscribieron las formas geométricas de sus mitos, y por las tradiciones orales que los recogen. Creció en Las Delicias, un pueblo a la orilla del río Táchira, al noroccidente de Venezuela, oyendo la lengua del agua sobre las piedras, pero sólo las recobró en su memoria cuando llegó a vivir a París en la década de los 80 y comenzó a utilizarlas como alfabeto para crear su propio universo, con una conciencia que lo devolvía al origen, al conocimiento de que todo está escrito en las piedras que no sólo yacen en el lecho de los ríos, sino flotan en el curso de los cielos.

La mítica araña Wale’kerü, que aparece en el título de esta exhibición, enseñó el arte del tejido a la gente Wayúu, los pobladores nativos de un territorio que se extiende en la frontera entre Colombia y Venezuela, y Milton Becerra, de abisal curiosidad, retoma su hilado y lo aúna a la comprensión de que el universo entero es un tejido de cuerdas luminosas que vibran de un modo que se manifiesta en diversas formas materiales. Por ello, en sus estructuras hay un eco de esos modelos de la física cuántica que buscan armonizar las leyes que rigen el macrocosmos –el movimiento de estrellas, planetas y galaxias- con los acontecimientos del microcosmos, no menos infinito, en el interior de las partículas más pequeñas de la creación.

Fue en la Ciudad Luz –uno de los lugares entre los cuales hoy vive– donde por primera vez conjugó rocas y cuerdas en una instalación que dispuso a la entrada de la XI Bienal de París, como una invocación a la naturaleza, la fuente primordial de donde también provienen nidos y laberintos en su obra, siempre tensados o estructurados con hilos.

Entre las alusiones hipertextuales de las piezas exhibidas en Wale’kerü. Líneas de luz también está también contenido el Renacimiento. Ha recibido el legado del matemático y artista Paolo Uccello, que como narra Vasari, vivía obsesionado por el punto de fuga, y buscaba la perfección en la perspectiva no como sus contemporáneos para narrar historias, sino para representar la máxima dimensión de la profundidad. Incluso más que el famoso mosaico de Uccello que está en el suelo de la Plaza de San Marcos, en Venecia y donde los prismas hexagonales atravesados por una cuerda sugieren la dimensión de lo tridimensional gracias a la perspectiva y a los colores; le interesa el mazzocchio que Uccello pintó muchas veces y que Leonardo dibujó: “En esa primera estructura espacial modular las formas se repiten de un modo que crea el máximo número de aristas posibles”. Repetición, profundidad, y suma de aristas proyectadas al infinito y acentuadas por la alternancia de colores –claro, oscuro, como el tablero de ajedrez- son aspectos clave en sus piezas. No hay que olvidar que el mazzocchio se incorporó en un tipo de tejido renacentista –intarsia- y de trabajos en madera donde los tonos de diferentes colores funcionan como piezas unidas, pero son independientes, a modo de un rompecabezas.

Por supuesto, en sus composiciones es ineludible ver igualmente el conocimiento de los hallazgos formales del cinetismo y particularmente de las indagaciones de la naturaleza del color irradiado en el espacio. Pero desafiando la consigna de los grandes cinéticos, que buscaban eludir toda referencia figurativa al mundo existente, las instalaciones y esculturas de Milton Becerra contienen la aparente paradoja de representar lo invisible a nuestros ojos: reflejan aquellos comportamientos de la materia que no vemos porque suceden en escalas visuales que escapan a nuestra percepción, y que sin embargo equivalen a una suerte de cordadura del universo. De hecho, el poder sugestivo de sus artefactos de visión –porque en eso coincide con las exploraciones de Marcel Duchamp- radica en que apelan a la memoria inconsciente de la humanidad, de un modo que evoca las formas de patrones geométricos arquetípicos, o las de herramientas universales –como los telares– que se remontan al neolítico, pero también a los juegos renacentistas de la perspectiva y el color, y a postulados teóricos como la teoría de las supercuerdas, que explica que todas las partículas y campos físicos están modeladas como vibraciones de delgadas cuerdas supersimétricas, que se mueven en un espacio-tiempo de más de cuatro dimensiones.

La representación aquí es en realidad un modo tridimensional de pintar la trama del universo, si se piensa que en lugar de trazar líneas sobre el plano, templa cuerdas sobre el espacio, evocando modelos de supersimetría, y provocando en el espectador la experiencia de percibir que las formas son también estados vibracionales, irradiaciones de energía. Por eso, en estas piezas tridimensionales de Milton Becerra no sólo hay rastros de técnicas y mitos asociados a la memoria de los telares milenarios y yuxtapuestos, y aprendizajes que contienen las figuras con las que Uccello se aproximó a la retícula de la realidad y el legado de figuras como Cruz-Diez o Soto; o el mismo eco de los modelos de la física cuántica que buscan armonizar las leyes que rigen el macrocosmos –el movimiento de estrellas, planetas y galaxias- con los acontecimientos del microcosmos, no menos infinito, de las partículas más pequeñas de la creación. Sus obras abren una suerte de pasajes geométricos multidimensionales. El artista deposita en ellas una miríada de referencias, pero sobre todo, la posibilidad de difundir la energía que concentran al espacio que las rodea a través de las sombras cambiantes y de las irradiaciones de colores en incesante transformación a lo largo del día.

“El tejido –asegura- no es una cosa simple”. Los hilos de color, tensados a la máxima tensión en estas pequeñas esculturas contemporáneas, provocan vibraciones en cualquier lugar en el que se encuentren.

Estamos ante piezas tridimensionales geométricas que al instalarse en un lugar específico nos hablan de la arquitectura del mundo, pero no menos, del espacio interior. Funcionan como objetos trascendentes: nos conectan a la visión de una unidad que está más allá de las mismas obras y que –si se quiere– para decirlo de un modo platónico, remiten a la forma de todas las formas.

Cada espacio-tiempo se transforma bajo la acción de lo que enseñó la mítica Wale’kerü: a imitar el tejido del universo con hilos de luz. Dueñas de una lúdica poderosa –que invita al juego visual e incluso incita el sentido del tacto– de cada una de sus esculturas surge finalmente un modo de contemplación que se acerca al asombro del cual nace la filosofía, y aprovechando la huella de historias del arte que van del precolombino al renacentista y a la abstracción geométrica o a la indagación en los campos de color, irradian una energía que es tan cambiante como placentera. Hay que observarlas en el juego de las luces y movimientos del entorno, para escuchar los inaudibles sonidos que contienen, la celebración del incesante nacimiento de las formas que contienen y producen. Lo que nos revelan en último grado está sintetizado en su afirmación: “La forma existe porque hay espíritu”.