Exhibition Close-Up: “Exodus: Alternate Documents”

Curators Willy Castellanos and Adriana Herrera on art, history, and the 1994 rafter crisis

CubanArtNews.com | Published: October 30, 2014

http://www.cubanartnews.org/news/exhibition-close-up-exodus-alternate-documents/4072

TEASER:

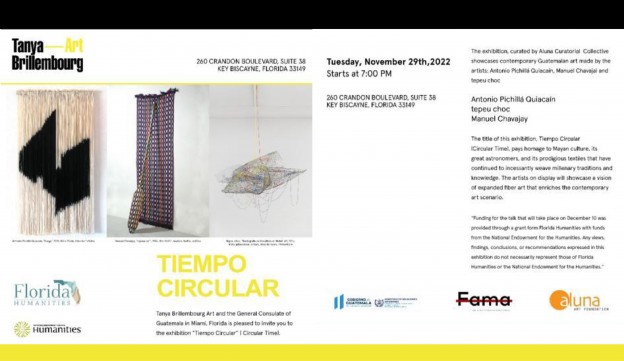

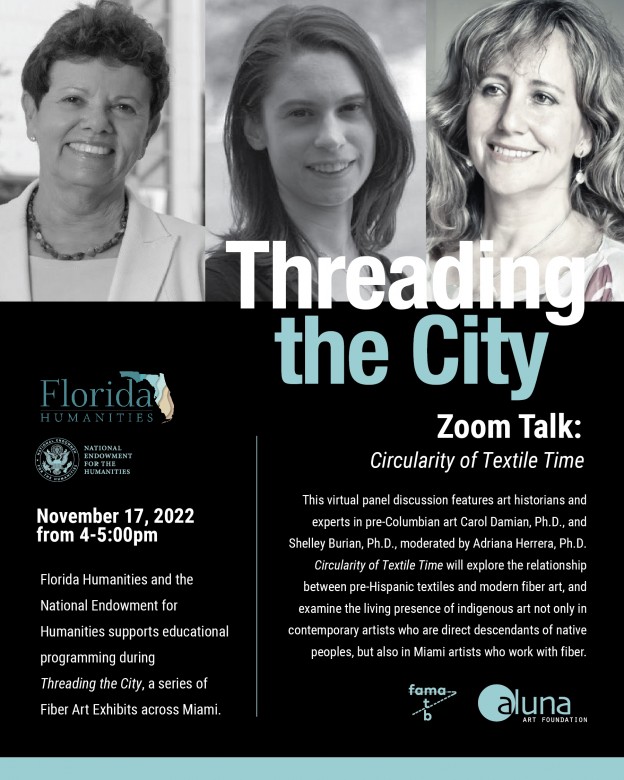

As the exhibition Éxodo: documentos alternos (Exodus: Alternate Documents) draws to a close this week at the Centro Cultural Español in Miami, we finally caught up with Guillermo “Willy” Castellanos and Adriana Herrera of the Aluna Curatorial Collective for an email conversation about the show. Answering individually and together, they provided a provocative overview of the exhibition and the thinking behind it.

What was the genesis of Exodus: Alternate Documents? How did it begin?

WILLY: Several moments precede the project. The first was the spontaneous photographic documentation I did on the Havana coast in the summer of 1994, during the turbulent days of the “Rafter Crisis.” With no intentions of exhibiting or publishing, the series was built from documentary pictures, a genre that particularly interests me in my studies of art history.

I chose 80 images to form the essay Rumbo Norte, más allá del Muro Azul, whose title comes from a short piece I wrote, about three years later, while living in Argentina. The work remained unpublished for nearly twenty years.

ADRIANA/WILLY: In 2012, Aluna Curatorial Collective inaugurated the PhotoAmerica section in the Arteamérica fair with Éxodo: una página extraviada de la historia, an installation of 30 photos. The idea was to insert into the archives of history this version—this “little history”—of the Cuban exodus, and with it try to reference every exodus across the world through these individual accounts. Since then, the project has taken on a more reflexive focus, questioning not only the social and cognitive authority of photography but the very concept of “History” as a single and totalizing narrative.

No less important was the emotional connection we established with people. That small space became an impromptu place for the testimonials of rafters who, in the presence of the images, wanted to tell their stories, and even offered to lend photographs and even objects related to their experiences. It was there that we had the idea of expanding the project.

Willy, your 1994 photos are the core of the exhibition, but it goes beyond that.

WILLY: The documentary record of the exodus was only the starting point for the creation of a scenario that would provoke the collective memory. The series that gives title to the project—Documentos alternos, 1994-2012—starts from this paradoxical power of photography to mythify history and at the same time expose the medium’s own contradictions. The photos express “my” version of the events, and at the same time my own inability to know, for sure, what happened there. So within the limits of the gallery, the exhibition itself is responsible for questioning this authority.

The photos have been presented in two different ways: first, as a documentary record, presented in a traditional way in black-and-white prints; and then in installations with intervening texts, 20 years later. The use of tracing paper in the second presentation reinforces the sense of a “membrane,” or layer of meaning, in the process of reconstructing history. The projections that these copies create on the wall evoke for us the contradictions of the image and its alternate versions, the original and the copy, or the picture and its reflection.

The texts that appear as captions demonstrate the inadequacy of visible data and the possibility that any interpretation could be traversed by fictions, tales, and reconstructions of all kinds. In Exodus, the works become the support for the living experience, in a fragmented reconstruction that includes the voices of those who tell their stories or leave traces of them in the exhibition space.

ADRIANA/WILLY: Éxodo: documentos alternos combines artistic and documentary practices. We use live testimonials, photography, and video interviews as documentary genres, and we’ve combined them with video art, artists’ installations, and other installations. This mixture was conceived as a curatorial exercise in the production of meaning and collective intervention.

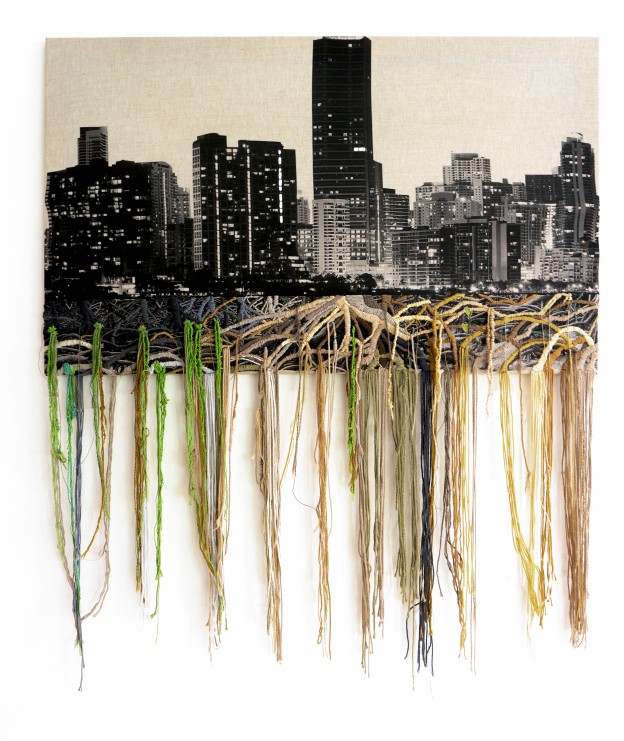

The project is shown in a gallery with alternative materials, such as industrial cables and struts, used in a work created by the artist Lili (ana), as well as advertising circulars, fabrics and prints on vinyl, tires, and cork boards and white boards for writing. More than an exhibition, the gallery became a workspace open to all rafters. Some works required their participation and will only be completed when the show is finished. In the work Album, for example, we encourage people to leave their own photographs of the exodus.

In parallel, we built a one-person room for video-shooting, where it’s possible to record, in private, a personal testimonial. With the support of cultural anthropologist Ariana Hernández-Reguant, we had an open-mike session with a group of rafters, where we recorded their narratives of the journey that will remain as materials in the exhibition.

Two Cuban-American artists, Coco Fusco and Juan-Sí González, were also invited to create installations.

ADRIANA/WILLY: As curators, we’re interested in the convergence of multiple voices and points of view. The idea of building a scenario out of documentary-based works led us to think about an open archive, not formed by a single voice or perspective. We also wanted to include some documentary images taken from different perspectives of space and time.

We had Rumbo norte, Willy’s series of photos taken on the coast off Havana. And also Rosa Náutica by Juan Sí González, which perfectly evokes the experience of one who approaches it from “the other side,” flying with los Hermanos al Rescate (Brothers to the Rescue) over a sea full of rafts, some of them castaways, some marked by death. Rosa Náutica includes the film record of his own volunteer experience in these aircraft, as the record of a poetics so violent as to be deeply moving: the image of a raft that little by little sinks into the sea.

The drifting rafts are projected not only on the wall but are duplicated on a surface created from mirrors and sea salt, suggesting the infinite dimension of the ocean. To stand before the scene of a raft covered with water is a way of returning to that moment of actual collapse, a way to obliterate time and look, not an object that disappears, but at the vast odyssey of an exodus that never seems to end. On the opening day, a few steps from the CCE Miami [where the show was presented], a raft from Havana made landfall, unlike others that week, whose bodies were not recovered.

ADRIANA: Coco Fusco´s installation Y el mar te hablará (And the Sea Will Speak to You) creates an immersive environment that dissolves the outside world and the present time. The artist places the viewer—who should remove their personal belongings and go barefoot into the projection space—on the surface of a drifting sea. In that dark space, the “outside” ceases to exist; the only perception is of the film that chronicles the rafter’s journey back to the island. Meanwhile she shares, as if in an intimate diary, the course of her thoughts as she faces death.

You cannot see Fusco‘s film without getting involved in it. The viewer sits not on a chair, but in the inflatable rafts like those the rafters launch into the sea. This experience involves the body of the spectator as an integral part of the work, transported to the drifting sea. The memory comes from a woman who returns to bring back her mother’s ashes.

The experience of watching (and listening to) Willy´s installation Pies secos, pies mojados (Dry Feet, Wet Feet) is very moving. First, from a distance, your eyes compose and complete the scene of the immensity of ocean. It is composed—according to the Gestalt principle—because the photographs are fragmented by intervals of emptiness, which dilute the images so completely that the initial impulse is to reconstruct the sea on the horizon. A sea with no name that first appears tranquil, but seen more closely reveals clusters of incipient storm clouds.

The horizon is a vast sea occupying the entire wall, the entire field of vision, but it’s fragmented. Each fragment rests on acrylic boxes forming a sequence of sand and water: dry feet, wet feet. So the installation shows with formal, almost minimalist beauty, the elements of the exodus: water, absence, horizon, uncertainty, empty, threatening storm, infinitely adrift…

But when the viewer comes closer and is right in front of the installation, what was invisible so far now appears: the acoustic dimension. And the voices of the rafters are heard in the instant that concentrates everything: the moment of departure. It is the sea, interrupted by fragments of emptiness and voices of those who are leaving (and whom we don’t see), and those who have left (and we know nothing about them). All this multiplies the evocative power of the work. The visual evocation has no geographical referents but the aural documentation (by filmmaker Luis Guardia) includes the actual instant of departure and the immense tension between the anxiety of the journey and the longing for what lies beyond the horizon: some place to build life again.

The video Muro (Wall, 2014) by emerging artist and animator Manuel Andrés Zapata contains a poetics that uses two elements in a continuous movement and superimposition: water and stone. His work is based on visual documentation of an extensive wall that Willy shot off the coast of the Mar del Plata in Argentina, for him the place afuera de la isla, away from the island. Photos are an unconscious evocation of what he saw in the sea around the island, with greater intensity than ever when he documented the exodus: a big blue wall.

It’s now 20 years since the balsero crisis. What do you hope the project will achieve?

ADRIANA/WILLY: As a space for interaction and sociocultural resuscitation, we’re motivated by the possibility of extending the margins of public participation, including the expectations usually associated with minorities that are often have little to do with art projects. Our challenge now is to get these people to attend and actively join the project we’ve organized.

The exhibition allows them to reflect about their own history and personal identity. Exodo: documentos alternos attempts to preserve the collective memory of one of the most moving events of contemporary Cuban history, to show that the past is not a closed case but a process that’s constantly being rewritten and reinterpreted. It’s the equivalent, in a practical sense, to returning that power to the voices of people who lived through the events. In this way, from a space of art comes an exercise that reaffirms the value of “small histories” above the official versions inscribed from a base of power and its ramifications.

Éxodo: documentos alternos closes tomorrow, October 31, at the Centro Cultural Español in Miami (CCEMiami).

SPANISH

Exposición en Primer Plano: Éxodo: documentos alternos

Publicado enOctober 30, 2014 |CubanArtNews.com | Espanol

http://www.cubanartnews.org/news/exhibition-close-up-exodus-alternate-documents/4072

A punto de cerrar Éxodo: documentos alternos en el Centro Cultural Español in Miami, conversamos con Guillermo “Willy” Castellanos y Adriana Herrera, de Fundación Aluna, sobre la muestra. Ellos ofrecen una mirada de la muestra desde su concepción.

Cuál fue la genesis del proyecto?

WILLY: Varios momentos anteceden al proyecto Éxodo: Documentos Alternos. El primero fue la espontánea documentación fotográfica que hice en las costas de La Habana en el verano del 94, durante los días convulsos de la “Crisis de los Balseros”. Sin intenciones de exponer o publicar, la serie se fue construyendo día a día con fotos de estricto corte documental, género que me interesa particularmente en mis estudios de historia del arte.

Elegí casi ochenta imágenes para formar el ensayo Rumbo Norte, más allá del Muro Azul, cuyo nombre viene de un texto breve que escribí sobre el tema tres años después, cuando vivía en Argentina. El trabajo se mantuvo casi inédito por veinte años.

ADRIANA & WILLY: En 2012, Aluna Curatorial Collective inauguró con Éxodo: una página extraviada de la historia la sección de PhotoAmerica en la feria Arteamérica. En un montaje de 30 fotografías, pudimos mostrar un material prácticamente inédito. La idea era insertar en los archivos de la historia esta versión –este pequeño relato- del éxodo cubano, apelando con ello a todos los éxodos del mundo a través de sus relatos particulares. Desde entonces, el proyecto tuvo un enfoque tan histórico como de reflexión documental, destinado a enjuiciar la autoridad social y cognoscitiva no solo de la fotografía, sino del propio concepto de “Historia” como relato único y totalizador.

No menos importante fue la relación afectiva que establecimos con la gente. Ese pequeño espacio se convirtió en un lugar improvisado para el testimonio de los balseros que, ante la presencia de las imágenes, querían contarnos su historia, e incluso, ofrecernos a modo de prestamos, fotografías y hasta objetos testimoniales. Fue ahí que surgió la idea de ampliar las dimensiones del proyecto.

Willy, tus imagines de 1994 son el eje de la muestra, pero ésta va mucho más allá. Cuál es su concepto?

WILLY: El registro documental del éxodo fue sólo el punto de partida para la creación de un escenario que provocara la recolección de la memoria colectiva. La serie que da título al proyecto –“Documentos alternos”, 1994-2012– parte de ese paradójico poder de la fotografía como instancia que mitifica la historia, y a la vez, exhibe las marcas de sus propias contradicciones. Las fotografías expuestas expresan “mi” versión del acontecimiento y al mismo tiempo, mi propia imposibilidad de saber, a ciencia cierta, lo que ahí ocurrió. De modo que dentro de los límites de la galería, la propia exposición se encarga de poner en duda esta autoridad.

Las fotografías han sido expuestas de dos maneras diferentes: primero, como registro documental -presentadas del modo tradicional en impresiones blanco y negro–, y luego en instalaciones intervenidas con textos, veinte años después. El uso de un papel transparente tipo película en las segundas, refuerza el sentido de “membrana” o de capa de significados en el proceso de reconstrucción de la historia. Las proyecciones que generan en la pared este tipo de copias, nos evocan las contradicciones de la imagen y sus versiones, del original y de la copia, o de la fotografía y su reflejo.

Los textos que aparecen como pie de fotos, muestran la insuficiencia del dato visible y la posibilidad de que cualquier interpretación se encuentre atravesada por ficciones, relatos y reconstrucciones de todo tipo. En Exodo, las obras se convierten en el soporte de la experiencia viva, en una reconstrucción fragmentada que incluye las voces de quienes cuentan su historia o dejan rastros de ésta en el espacio expositivo.

ADRIANA & WILLY: Éxodo: documentos alternos combina prácticas artísticas y documentales. Usamos el testimonio en vivo, la fotografía y la video-entrevista como géneros documentales, y los hemos combinado con videoarte, con instalaciones de autor, y con otras instalaciones. Esta mezcla se concibe como ejercicio curatorial de producción de significados y de intervención colectiva.

El proyecto se despliega en sala con materiales alternativos como sistemas de cables y tensores industriales –un procedimiento creado por la artista Lili(ana)–, aditamentos publicitarios, telas e impresiones en vinil, neumáticos, y tableros lisos para la escritura o forrados con planchas de corcho. Más que una exposición, la galería se convirtió en un espacio de trabajo abierto a todos los balseros. Ciertas obras requieren su participación y solo estarán finalizadas cuando termine la muestra. Así, en el la obra Álbum por ejemplo, invitamos a las personas a que dejen sus propias fotografías del éxodo.

Paralelamente, construimos en sala una cabina individual de video-filmación, donde es posible grabar en privado el testimonio personal. Celebramos –con el apoyo de la antropóloga cultural Ariana Hernández-Reguant—una sesión de micrófono abierto con un grupo de balseros, donde grabamos las narraciones de la travesía que quedarán como materiales de la exposición.

Como curadores, invitaron a dos artistas cubano-americanos: Coco Fusco y Juan-Sí González, para crear instalaciones a incluir en la muestra. Por qué?

ADRIANA & WILLY: Como curadores, nos interesa la convergencia de múltiples voces y miradas. La idea de construir un escenario con obras de base documental nos llevó a pensar en un archivo abierto, no conformado por una sola voz o una sola mirada. También queríamos convocar una suma de imágenes documentales tomadas desde diversas perspectivas de espacio y de tiempo.

Teníamos Rumbo norte, la serie de fotografías tomadas en las costas de La Habana, así que Rosa Náutica de Juan Si González, era perfecta para evocar la experiencia que él vivió desde “la otra orilla”, sobrevolando con los Hermanos al Rescate, un mar lleno de balsas, a veces con náufragos, a veces marcadas por la muerte. Rosa Náutica contiene el registro fílmico de su propia experiencia de voluntario en esos aviones, como marco de una poética tan violenta como conmovedora: la lenta imagen de una balsa que poco a poco se hunde en el mar.

Las balsas a la deriva no sólo se proyectan en la pared, sino que se duplican en una superficie creada con espejos y sal marina que sugiere la dimensión infinita del océano. Estar ante la escena de la balsa cubierta por las aguas, es un modo de volver a ese instante del hundimiento real como forma de aniquilar el tiempo, y mirar, no un objeto que desaparece sino la vasta odisea de un éxodo que nunca parece acabar. El mismo día de la inauguración, a unos pocos kilómetros del CCEMiami, arribó una balsa con hombres y mujeres que lograron llegar; una suerte que no tuvieron otros balseros, esa misma semana, cuyos cuerpos no pudieron recobrarse.

ADRIANA: Y el mar te hablara, la instalación de Coco Fusco, crea un ambiente envolvente que disuelve el mundo exterior y el tiempo presente. La artista sitúa al espectador –que debe despojarse de sus objetos personales y entrar descalzo al espacio de proyección- en la superficie de algún mar a la deriva. En ese espacio oscuro, “el afuera” se detiene, solo se percibe el filme que narra su viaje de regreso a la isla. Mientras nos comparte –como diario íntimo- el curso de sus pensamientos en ese momento que contiene el enfrentamiento a la experiencia de la muerte: lo que lleva consigo, en la travesía, son las cenizas de su madre.

El filme de Fusco no solamente se ve, sino que te involucras dentro de él. El espectador se sienta, no en una silla, sino en las cámaras inflables como las que justamente usaron los balseros para lanzarse al mar. Esa experiencia involucra el propio cuerpo del espectador, lo integra a la obra, lo transporta a la deriva de un mar, a la memoria en deriva de una mujer que regresa para llevar los restos de su madre. Esta experiencia, es de algún modo intransmisible.

La experiencia de ver (y escuchar) la instalación Pies secos, pies mojados, de Willy, es conmovedora. Primero, desde una cierta distancia, tus ojos componen y completan la escena de la inmensidad del océano. La componen –siguiendo el principio de la Gestalt- porque la fotografía está fragmentada con intervalos constantes de vacío que desde lejos se diluyen “casi” completamente, así que la percepción inicial es la de reconstruir el mar en el horizonte. Un mar sin nombre, sólo el mar, que primero nos parece tranquilo, pero visto con mayor atención revela los cúmulos de nubes de una tormenta latente.

El horizonte es el de un mar inmenso que ocupa toda la pared, todo el campo de visión, pero está fragmentado. Cada fragmento descansa sobre cajas acrílicas que forman una secuencia de arena y agua: pies secos, pies mojados. Así, la instalación cifra con enorme belleza formal, casi minimalista, los elementos del éxodo: agua-ausencia-horizonte-incertidumbre-vacío-tormenta que amenaza-deriva infinita…

Pero cuando el espectador se acerca aún más y está exactamente frente a la instalación, aparece lo que hasta entonces era invisible: la dimensión acústica. Y escucha las voces reales de los balseros en ese instante donde todo se concentra: la inminencia de la partida. Es el mar, intervenido por fragmentos de vacío y las voces de todos aquellos que se van a ir (y que no vemos) y que se fueron (y de quienes nada sabemos) multiplica el poder evocador de la obra. La evocación visual no tiene referentes geográficos mas la documentación auditiva (cortesía del documentalista Luis Guardia) contiene ese instante real de la partida y la alta tensión entre la angustia de la travesía, y el anhelo por lo que hay mas allá del horizonte: algún lugar donde refundar la vida.

El video “Muro” (2014) del artista y animador emergente Manuel Andrés Zapata, contiene una poética que usa dos elementos en continua superposición y movimiento: el agua y la piedra. Su trabajo parte de la documentación visual de un extenso muro que Willy fotografió en las costas de Mar del Plata, Argentina, para él el lugar de un “afuera de la isla”. Las fotos son la evocación inconsciente de lo que vio en el mar que rodeaba la isla, con mayor intensidad que nunca cuando documentó el éxodo: un inmenso muro azul.

Veinte años nos separan de la crisis de los balseros. Qué ha logrado el proyecto?

ADRIANA Y WILLY: Como espacio de interacción y reanimación socio-cultural, nos motiva la posibilidad de ampliar los márgenes de participación, incluyendo expectativas vinculadas con minorías habitualmente alejadas del proyecto artístico. Nuestro gran reto ahora es lograr que estas personas asistan y se incorporen activamente al proyecto que hemos organizado.

La exposición les permite crear un momento de reflexión sobre su propia historia y su identidad personal. “Exodo: documentos alternos”, intenta conservar la memoria colectiva sobre uno de los hechos más conmovedores de la historia cubana contemporánea, para demostrar que el pasado no es un caso cerrado, sino un proceso en constante reescritura y reinterpretación. Ello equivale, en un sentido práctico, a devolverle ese poder a las voces de aquellos que vivieron los hechos. Así, desde el espacio del arte, se concreta un ejercicio que reafirma el valor de las pequeñas historias ante las versiones oficiales que se escriben desde el poder y sus ramificaciones.

Éxodo: documentos alternos cierra Octubre 31, en el Centro Cultural Español en Miami (CCEMiami).